I’m recently returned from a weekend trip to Charleston, South Carolina. The heinous history of American slavery is plainest and rawest in the South, where whites fought longest to preserve it. And so I think of the region as something like Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire: an aging beauty, beguiling and a little perverse, with an abiding nostalgia – at least by some – for a past that is only half true.

Spanish moss on a tree in historic Charleston. Photograph by Mari Monteiro.

My sister and I ventured back to an antebellum city we had seen some twenty years ago. Charleston charmed us. Its core is known for its remarkable architecture – an array of stately homes that showcase changing taste from the early eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth. They comprise a parade of modest colonials, proud Georgians, Palladio-influenced Adamesques, august Greek Revivals, and fanciful but rarer Victorians. Providing setting for these homes is a maze of interconnecting green spaces punctuated with palms, live oaks, and Spanish moss that uncannily drapes itself over tree boughs every which way you turn. The city feels like one large garden.

China and Tea roses in front of the Middleton Oak, Middleton Place. Photograph by Mari Monteiro.

About twenty miles outside of Charleston, the house at Middleton Place, which dates to 1755, is sited on a large plantation. Here, the gardens, the oldest in the U.S., bloom all year long. The beginning of November, when we were there, marked the last of the China and Tea Roses that flower not far from the Middleton Oak, which predates the arrival of English colonists in Low Country. The coming early winter months promise a variety of camellias. Middleton Place’s bounty culminates each year in March or April, when blossoming azaleas set one hillside ablaze with fuchsia, pink, and purple. Throughout, the gardens present a vision of nature that is mapped, ordered, controlled, its schedule predictable, many of its rows of shrubbery and flowers symmetrically arranged and all neatly trimmed. The Middleton Garden, in this way, is a microcosm, a miniature version of a supposed European mastery over the New World.

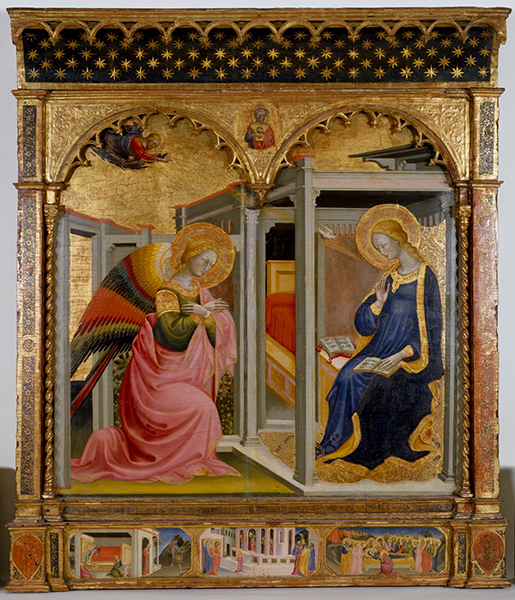

The Annunciation, by Bicci di Lorenzo and Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni, tempera and gold leaf on panel, ca. 1430. Image courtesy of the Walter’s Art Museum.

Before the large-scale arrival of Europeans in North America, medieval and Renaissance painters in Europe used nature as an emblem, investing symbolic meaning into it in depictions of religious scenes. I recently saw one example. In Bicci di Lorenzo and Stefano d’Antonio di Vanni’s fifteenth-century tempera and gold-leaf Annunciation altarpiece, now housed in Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum, the hortus conclusus, or enclosed garden, is emblematic of Mary’s virginity. Though the archangel Gabriel, God the Father, and the white dove representing the Holy Spirit penetrate the garden walls and Mary’s columned domestic space, her chastity remains uncompromised. She accepts the news of her immanent immaculate consumption with dignity, bowing her head toward her devotional reading and raising her hand in faint acceptance. The sculptural and heavily twisted columns that frame the panel act as yet another boundary, dividing the religious scene from our own secular space. Mary may have inspired worshippers in their own devotion, but hers is an unattainable piety. We see and stand before her, but we do not enter her sacrosanct space.

There are gardens like Mary’s in Charleston, too, enclosed not by the orders of piety but by the rights private property bestows. The sign at one open gate in the city center reads “Beyond this point, by invitation only.”

An interior hallway in Peter Zumthor and Piet Oudolf’s Serpentine Gallery pavilion. Image courtesy of designboom®; photograph by Walter Herfst.

The garden inside the 2011 Serpentine Pavilion. Image courtesy of the Serpentine Gallery; photograph by John Offenbach.

The hortus conclusus, however, is not always off limits. For the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, which came down last month, architect Peter Zumthor and designer Piet Oudolf welcomed the public into a garden space of reflection and quiet conversation, excluding not the public but the bustle and automotive traffic of London. Photographs of the temporary space show a double-shelled building, austere like a medieval monastery. Going toward the light at the open doorways of the inner shell, visitors entered an interior space open to the sky and views of the trees of Hyde Park that surrounded it.

The enclosed garden was open.