The world appears different through glass. A window frames a view. A lens refracts and focuses light. Our eyes, too, have light-bending lenses, shape-shifters that widen to focus close objects into images on our retinas and narrow for distant views. And so vision is embodied; it’s in our bodies. Our eyes and brains recognize the visual landscape of color and shape and scale with a fluency that often, though not always, naturalizes vision, making it appear forgettabley seamless. Looking through the glass of a window or that of a lens that has been ground and polished can let us see out, or better. But this glass is also an added layer between our own embodied viewing and the world.

The wall drawings that make up Blue Sun, Victoria Haven’s current exhibition inside the pavilion at the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park, take their color from the pulsing blue dots that sometimes appeared in place of the sun as the artist filmed Seattle’s South Lake Union neighborhood from her studio over a ten-month period. They are, in this way, artifacts not of her own embodied vision or even mutable memory but of how her camera saw and recorded.

Installation view of Blue Sun, 2016, Victoria Haven, acrylic, 57 x 14 ft., Seattle Art Museum, 2016 Commission, Photo: Natali Wiseman. Image courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

Installation view of Blue Sun, 2016, Victoria Haven, acrylic, 57 x 14 ft., Seattle Art Museum, 2016 Commission, Photo: Natali Wiseman. Image courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

Geography, displacement, and memory underlie much of Haven’s work, but given the bold, crystalline forms it often takes, you might not at first recognize these as her subjects. “…[S]pare as it might be,” Claire Dederer writes of her work in an essay that accompanied the artist’s 2011 companion Seattle and Portland exhibitions Hit the North, it “is as layered with reference and memory as an archaeological site. Her past, like rabbit-shaped fingers in front of flashlight, makes shadow appearances in her work.”

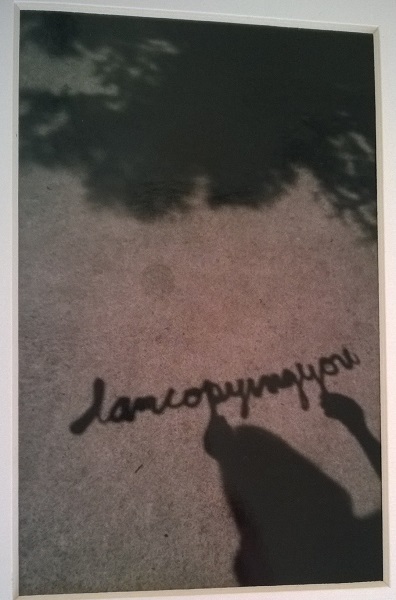

I know these shadow appearances. Above my desk, framed and hung, is a postcard picture Haven and Michael Fox made a few years ago. “I am copying you,” a cursive script scrawls across the middle of the composition. It looks as though two hands are poised just below the text, where the “p” and second “y” of the words loop low. But you’re not looking at hands themselves, only their shadows. The flat color value of these shadow hands creates a disorienting ambiguity so that it’s hard to identify them, especially the one on the left, with certainty. The cast shadows of a tree and of a head and torso to whom the apparent hands belong copy the unseen shapes of leafy tree and figure, simplifying and bending them to the flat surface of a stone or concrete ground that Haven’s picture takes as its subject. Here is mirroring and distortion, I think, as I look up at it often. And then, too, there is the doubling and distortion of the photograph itself.

At the sculpture park, in this more recent piece, Haven’s past and the artifacts she collects appear anew not as literal shadows but as faceted, hollow blue shapes that float, weightless, across a white wall. Their precise lines and varying shades can trick your eye into believing you’re looking at a three-dimensional form, but it’s just a flat surface you see. Colors and angles echo the Olympic Mountains out to the west, especially the way the peaks appear in the sharp light of midday. And Blue Sun’s open centers recall the hollow of Isamu Noguchi’s ring-shaped Black Sun, a sculpture a couple of miles east and north that the Seattle grunge band Soundgarden made famous in the 1990’s. From its perch at Volunteer Park, Noguchi’s black granite sculpture frames the Space Needle several miles away, making borrowed scenery of the Seattle icon. The shapes in Haven’s Blue Sun have hollows too, but there is no architecture or atmosphere in their openings, only an emptiness that seems to suggest that this sun’s movement across the sky, across the wall, is too momentary to frame anything in its flicker and flight. Haven herself has had to keep changing her vantage. She’s been in seven studios in eighteen years, swept to and fro in the rush of Seattle’s development boom. The place where she works and from which she looks out at the city has been, over and over, a temporary one, relocated as buildings are razed and then others take shape and rise in their place.

Isamu Noguchi’s Black Sun, 1968, Brazilian black granite, 9 x 3 ft., Volunteer Park, Photo: Spike Mafford Photography. Image courtesy of the Seattle Office of Arts and Culture.

Blue Sun, aside from its own crystalline forms, also lets in literal shadows. On the sunny afternoon I spent at the sculpture park a few weeks ago, a long, segmented sliver of light and shadow cast itself along the bottom of Haven’s wall drawing. Its regular rhythm corresponded to the repeated cadence of glass and steel from the west wall of Weiss/Manfredi’s pavilion architecture. The building was throwing both light and its own shadow onto the wall.

When I stepped outside, I snapped a few pictures looking back through the pavilion’s glass walls. Later, indoors, when I could look at the images away from the dazzling afternoon light, I saw reflections from the outdoor chairs, the surrounding buildings, and the sky. They all cast their colors and shapes, but mutedly, more hazily, onto the transparent glass and, through it, onto Blue Sun inside. I had seen these things as I walked around that afternoon, but I hadn’t noticed them doubled in the glass.

My camera had made its own memory.

Blue Sun is on view at the Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park through March 5, 2017.