Others Who Were Here, Cris Bruch’s sparely installed exhibition that just came down at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, used looking and language to summon the expansiveness of eastern Colorado, where Bruch’s family worked as farmers in the early twentieth century.

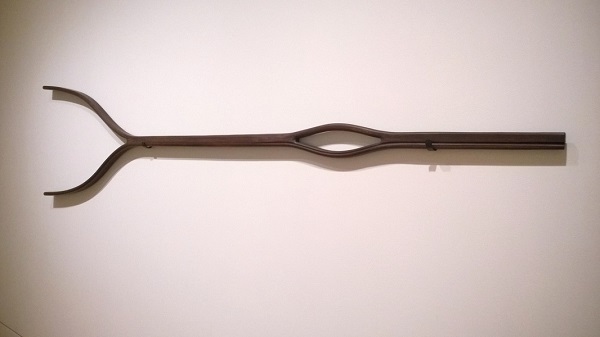

Titles and wall text worked in tandem with Bruch’s sculptures and installations to evoke a remembered and imagined landscape much bigger and far less peopled than the Frye’s white-walled and well trafficked galleries. Some of this the artist pulled off with scale. The sculptures Jack, Helve, and Harrow each hung on the wall like implements you could grab for a job. But though they are named for tools or parts of tools, they’re made of wood, not metal. They’re also outsized, many times larger than their namesakes, recalling the scale of childhood, when the adult knowhow of work and the body at work loom large and mysterious. Elsewhere, scale was diminished. The shrouded, mostly shin-high models of vernacular architecture that sat on the floor in the room-size installation Agra, Dresden, Firstview, Gem, Genoa, Leoti, Leoville, Weldona were meant to call to mind the grain elevators of the Great Plains. Later, I searched a map and found their names dotted across northeastern Colorado and northwestern Kansas. In the installation itself, I look out across the shapes and then down from above. “Imagine you’re a bird flying overhead,” a docent said as she led a group into the space, and as I moved past the outlines of buildings made small and ghostly, I imagined too.

Cris Bruch’s Weldona, Dresden, Limon, Leoville, 2015, flannel, fiberglass, and epoxy. Image courtesy of the Frye Art Museum. Photograph by Mark Woods.

Beyond scale, Bruch also works with how materials feel near the body. The steel skeleton and recycled church windows that make up Conservatory were left open or pulled apart, suggesting a receptiveness to light and air and space rather than the enclosure and shelter we usually associate with architecture. Meanwhile, the tight angles of Pent seemed to make the installation contract as I stepped through it. Inside, I felt like a steer in a corral, the smell of newly cut wood sharp and full in my nose.

Cris Bruch’s Conservatory, 2016, steel and recycled church windows. Image courtesy of the Frye Art Museum. Photograph by Mark Woods.

In her novel Housekeeping, Marilynne Robinson writes not of Bruch’s Great Plains but of Idaho, another landscape sparse of people but laden with memory. For the book’s narrator, Ruthie, Idaho’s mountains and forests and the homesteads that perch exposed and transient on and in them offer a corollary to her own internal landscape, solitary but beset with narrative. “The woods were full of…stories,” Robinson writes in Ruthie’s voice, musing, lonely, as she seeks out and waits for her aunt. “There were so many stories, in fact, that there must have been at some time a massive exodus or depopulation, for now there were very few families in the woods, even near to town—too few by far to account for such an enormous tribe of ancestors—even ancestors given, as these seem to have been, to occasional wholesale obliteration.” (Housekeeping, pages 156-157)

Bruch’s Others Who Were Here was also about landscape and narrative. But whereas in Housekeeping the ghosts of these obliterated people press their stories upon Ruthie, sidling up to her even as she tries to keep them at bay, even as she tries to ward them off with her own burnished memories of kinship and closeness, Bruch sought out ghosts and their tales. The stories he made over into new work, though, are only ever partial, pieced together from memories and objects left behind. He recognizes them for the fragments they are. “I know something about the circumstances of immigrants and migrants who were lured to the Great Plains and about historic events, the Dust Bowl and the grasshopper plagues, about booms and busts,” Bruch wrote in an accompanying wall text. “I know they worked awfully hard and that church was a very important thing for them. But there are gaps in what I know about my own family.” And of course, there were others who came even before, indigenous people, like the Arapaho, who remade the Great Plains into the giant grasslands with roaming bison herds and who were devastated in the so-called Indian Wars in the second half of the nineteenth century. Their stories, their continued presence in the Great Plains didn’t figure in Bruch’s narrative at the Frye.

What his pieces, his words, do remind me of is the landscape of my husband’s hometown in eastern Nebraska. In summer there, on sultry evenings, plagues of locusts call out from every direction beneath flashes of heat lightening; in winter, low, snow-heavy skies turn the daylight a muted yellow. There was hardly any of the color I associate with the great skies of the Midwest in Others Who Were Here. But you could find it inside the four vessels of Bruch’s Emollients: Ingram’s, Marinello’s, Purola, Velvatone, named for the four cosmetic brands that made these ointments. “The sculptures,” the artist wrote, “are three-times-larger versions of old cold cream jars I found in the midden behind a roadside museum in eastern Colorado that two of my great-uncles built. I thought of my grandma and aunts. They had a life of hard work in dry, windy country. A jar of cold cream was no doubt a luxury.”

Cris Bruch’s Emollients: Ingram’s, Marinello’s, Purola, Velvatone, 2016, blown glass. Image by the author.

And I, in turn, thought of the canisters that house ashes in artist David Maisel’s 2005 Library of Dust project. His photographs show the unclaimed cremated remains of patients from a psychiatric hospital in Oregon now blooming across the canisters’ copper surfaces. We speak of vessels like we do bodies, with their shoulders and necks. And so Maisel’s canisters and Bruch’s jars are each kinds of portraits, or likenesses. They’re also landscapes. As I looked past the milky outsides and down into the vivid cornflower blue of Bruch’s blown glass jars, I saw both the vastness of the Plains sky, the sky that brought the dry wind and the heat and the cold, and the grandmother or aunt who reached for the cream to soothe her skin, to offer herself a salve against this harsh weather that still sweeps across the Great Plains and still visits those who are there.

Cris Bruch: Others Who Were Here was on view at the Frye Art Museum from January 30th through March 27, 2016.