At the Seahawks-Vikings football game several weeks ago, players exhaled clouds of heat and moisture as they lined up for the snap. Their breaths swelled from their mouths, spread away, and then disappeared into the frigid Minnesota air. Welcome to Jupiter, sportscaster Al Michaels quipped.

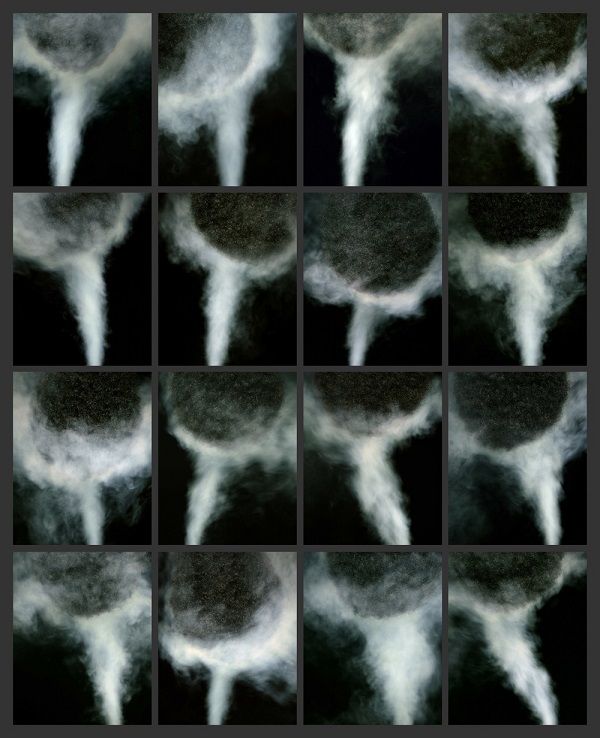

Demetrius Oliver’s Eclipse, 2006-2008, digital chromogenic print mounted on Sintra.

Image courtesy of the Henry Art Gallery.

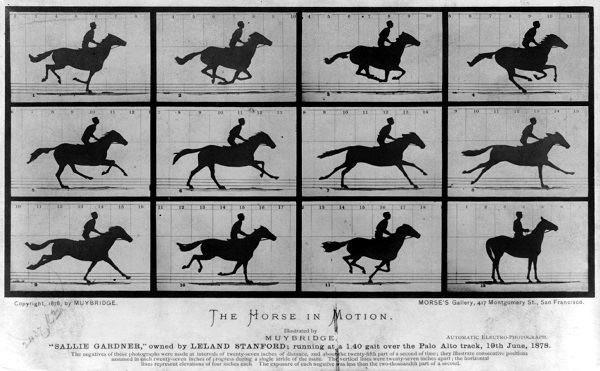

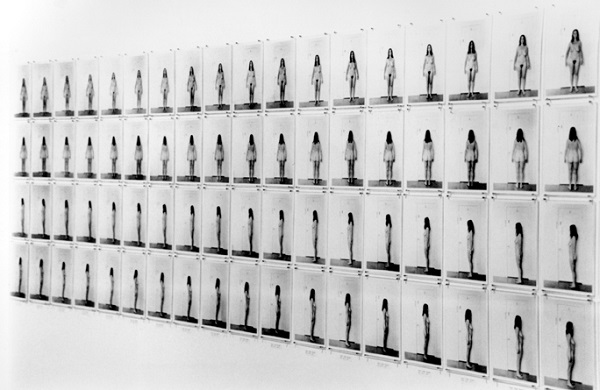

A galaxy away, at the Henry Art Gallery, artist Demetrius Oliver’s Eclipse presents sixteen black-and-white photographs, oblique self-portraits of the African-American artist, in a tidy four-by-four grid. But much as you’d like to, you can’t read them as you would a scientific chart, a neat unfolding of instances over time. They are unlike the highlights of a come-from-behind athletic victory, or the successive shots of Eadweard Muybridge’s nimble horses accelerating to make the beginnings of cinema at the end of the nineteenth century, or even the daily photo documents of Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), which methodically show her figure, front, back, and sides, as it slowly diminishes in response to her weeks-long crash diet. And, their title notwithstanding, Oliver’s photographs certainly don’t read like the orderly progress of an astronomical eclipse, with one celestial body moving toward, overlapping, and then obscuring another.

Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion, 1878.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division.

Eleanor Antin’s Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972.

Image courtesy of the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

No, in Eclipse, we see partial views of the round shape of Oliver’s head and his tight black curls from above, but either camera or head moves from image to image so that our relative position, our relationship to his figure, is always shifting away from and back toward. Meanwhile, a bright white cone of air sprays and spreads out around the surface in each, illuminating his head, limning it with a vaporous halo, and obscuring it, partly, beneath an opaque density that will soon dissolve. An eclipse, we know, is an alignment of two bodies before a viewer, but it’s also a struggle for the power of visibility, a question of which body gets seen and which falls out of view, if only for a moment. A thing eclipsed is that which falls into obscurity or decline. But the kind of linear narrative seen in lunar and solar movement, or athletic competition, or equine dynamism, or gradual weight loss, does not appear in Oliver’s photographs. We read in them not a sequence but a perpetual struggle, a black head and black hair coming forward into the light only to be shrouded by it, like a ghost from a nineteenth-century spirit photograph.

The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, like Oliver, insists on the black body over and over even as he fears for its dematerialization, even as he struggles against its becoming obscured in the myth-making of the American dream or, worse yet, brought down and pried open by the violence that is so often visited upon black bodies, especially black men, in our country. And in his recent book Between the World and Me, that ardent but tender letter to his teenage son, Coates won’t let the black body be lost either to the smoothness of politically correct language or academic erudition. “But all our phrasing—race relations, racial chasm, racial justice, racial profiling, white privilege, even white supremacy,” he writes, “serves to obscure that racism is a visceral experience, that it dislodges brains, blocks airways, rips muscles, extracts organs, cracks bones, breaks teeth. You must never look away from this. You must always remember that the sociology, the history, the economics, the graphs, the charts, the regressions all land, with great violence, upon the body.” (Between the World and Me, page 10)

In the mysterious photographs of Demetrius Oliver’s Eclipse, there is not the clear violence of the stand-your-ground laws and police brutality Coates writes about, nor the repeated head trauma that many professional football players, mostly African American, sustain. There’s just a black crown that won’t disappear into the white light.

Demetrius Oliver’s Eclipse is on view at the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle through April 10, 2016.