During the week, I look often from my office to the flickering work lights of a half-finished building south of Lake Union, where Seattle’s skyline is acquiring a new shape and solidity. The lights are distributed regularly throughout the building’s boxy frame, and they radiate in morning fog, pulsate in the fair skies of midday, and shine like beacons in midnight cloud and rain. The flickering is a trick of light and air. Once the building is enclosed in glass — I’ve watched, close at hand, construction workers installing large, tinted sheets of it along the façade, working their way up from the building’s bottom stories — it won’t beckon my gaze with the urgency of the apparition it appears to be now. It will have become a building, solid and substantial, and not a vision poised between becoming and being.

How long will it last?

Among the photographs, scaffolding, and graffiti of Hedonic Reversal. Image by the author.

As I’ve gazed south at this half-formed building these last months, I’ve been thinking of Rodrigo Valenzuela and his show, Future Ruins, at the Frye Art Museum, and especially his installation Hedonic Reversal. Here, 17 large archival pigment prints on Dibond hang on scaffolding, marks of graphite and ink hovering behind them like ghostly graffiti. Talking about these photographs when the show opened in January, Valenzuela referred to the artist Lucio Fontana returning to his studio in Milan after the bombings of World War II. He spoke, also, of the frequent earthquakes in Chile, where he grew up before emigrating to the U.S. in 2006. Frye Director Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker mentioned architectural follies and the pleasure in ruins Westerners have found from the eighteenth century forward.

One of the 17 photographs in Rodrigo Valenzuela’s installation Hedonic Reversal. Image by the author.

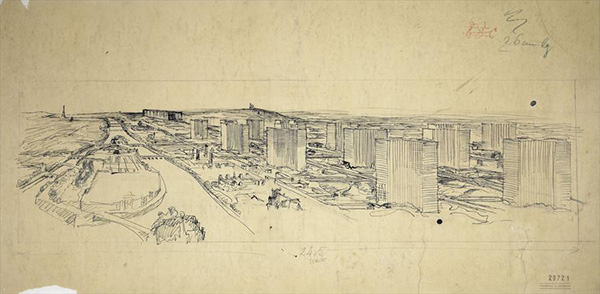

But in Hedonic Reversal I also see Le Corbusier and his plans for Paris, captured in ink drawings and black-and-white photographs of architectural models. The Swiss/French architect first showed his Voisin Plan, named for the French car manufacturer, in Paris’s city-planning rotunda in the Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau at the Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in 1925. Modern successor to Baron Haussmann and his radical nineteenth-century transformations of Paris that gave the city its characteristic apartment blocks and long boulevards, Le Corbusier called for the destruction of most of the buildings between the Seine and Montmarte. In their place, he proposed sixty-story cruciform towers that would occupy an urban landscape made regular and open. In one of his sketches of the Voisin Plan, the Eiffel Tower stands in the distance, a relic of nineteenth-century engineering and witness, now, to the developments of the twentieth.

The architectural model for Le Corbusier’s Voisin Plan for Paris, 1925. Image courtesy of Fondation Le Corbusier.

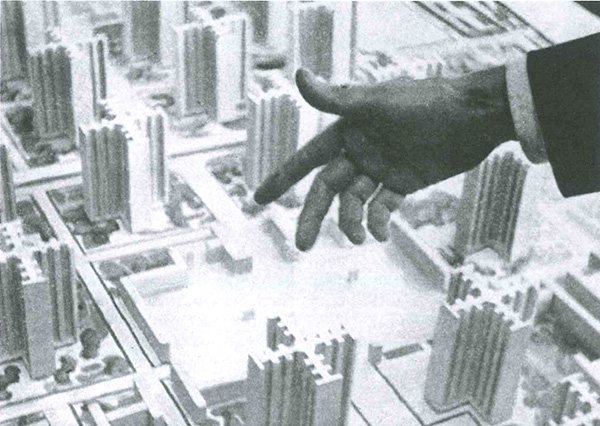

Architectural models are seductive visions of control. The journalist and activist Jane Jacobs wrote of Le Corbusier’s succession of urban schemes from the 1920s and ’30s, “…[H]is conception, as an architectural work, had a dazzling clarity, simplicity and harmony. It was so orderly, so visible, so easy to understand. It said everything in a flash, like a good advertisement…But as to how the city works, it tells…nothing but lies.” To Jacobs, Le Corbusier’s urban planning was an exercise in aesthetics that had little to do with the bustling, motley ballet of city life about which she writes so eloquently in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In a gesture, he proposed to sweep aside the city’s heterogeneous fabric in the name of height, light, progress, and a uniform architectural language.

Le Corbusier waves his hand in front of an architectural model of his 1925 Voisin Plan for Paris. Image courtesy of Strates: Matériaux pour la Recherche en Sciences Sociales.

In Hedonic Reversal, Rodrigo Valenzuela both makes and destroys this dream of progress, offering up, at the end, architectural models that have been fragmented, razed, and pulverized. The photographs contain allusions to their own making — photographs within photographs that serve as backdrops for the drama of wreckage in the foregrounds, a bar-coded sticker left on a piece of wood from the store where the artist purchased it, a little model of an ornate column supporting a wooden slab above, the artist’s footprints on the ground, and slivers of studio space left to frame these scenes of construction/destruction. There’s so much building in Seattle now that his plaster, wood, and Styrofoam models naturally feel like they’re about our city, but Valenzuela never lets you forget that Hedonic Reversal is a fiction staged to trigger visual pleasure as well as to provoke knotty trepidation about what we ourselves are making and unmaking.

Rodrigo Valenzuela’s Hedonic Reversal #7, inkjet print, 2015. Commissioned by the Frye Art Museum and funded by the Frye Foundation. Image courtesy of the museum.

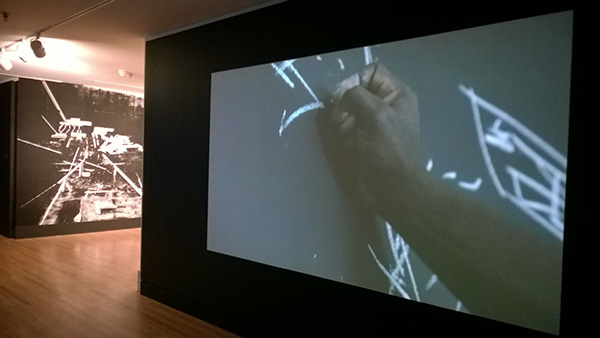

The other pieces in Future Ruins — all videos — are more explicitly about labor. In the transitional piece that hinges between the show’s two parts, a man is diagramming at a chalkboard. It looks as though he might be working through a mathematical proof or designing plays for a football team. What he’s actually doing is planning out how he and his fellow cleaners will make their way through a littered stadium, putting it in order before it’s left, once more, in a state of temporary ruin.

In that way, his work, like Valenzuela’s, is about a model and an ideal unmade.

A still from Rodrigo Valenzuela’s digital video El Sisifo with an image from Hedonic Reversal on the left, 2015. Image by the author.

Future Ruins is on view at the Frye Art Museum through Sunday, April 26. On Sunday, April 12, Director Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker will talk with geographer Barbara Heinzen about planning and ruins in an event called “Perspectives on Ruin Making.”