“Beauty is vapour from the pit of death.” (The Peregrine, p. 180)

For the last several months, I’ve been coming to the Henry Art Gallery most Wednesdays to read from a book about a hawk season in the fenlands of eastern England. To describe J.A. Baker’s The Peregrine as only that, though, would be to diminish it. Baker’s small book is extraordinary for the fineness of his observation, exquisite for the way his language summons color, temperature, light, movement, and longing. It is made all the more beautiful for the death that haunts its narrative. I had seen praise for it but hadn’t yet read it. Ann Hamilton: the common S E N S E was my pretext.

I read Baker’s book out loud to images of specimens from the Burke Museum of Natural History, printed on humble newsprint and bolted to the walls of the North galleries in piles, or to garments made from feathers, fur, or guts and presented in glazed metal carriages in a double-height gallery downstairs. These arranged skins, both the images and the finery, are like Baker’s writing, beautiful. As it is for The Peregrine, death is part of their marrow.

Reading in the North galleries at the Henry Art Gallery, December 2014. Photograph by Liz Patterson.

“…[H]e hung motionless, tensing and flexing his swept-back wings, dark anchor mooring white cloud…The wind could not move him, the sun could not lift him. He was fixed and safe in a crevice of sky.” (The Peregrine, p. 177)

Mostly, I read in the upstairs galleries, where images of animals gather suspended against white walls. There, my eyes adjust as light coming through the open skylights weakens and brightens. I hear the drone of the HVAC system, feel its draft, and pull a wool blanket — furnished especially for the exhibition — tighter about my lap. I read, each time, to an image at eye level. I like to feel the thin paper with my fingertips, to connect the trajectory of my voice to the reach of my hand. There isn’t a word of Baker’s that has struck me as false or misplaced, but sometimes I find a passage especially remarkable, and I copy it into a leather-bound notebook I share with other reader/scribes, repeating and slowing my delivery to match the pace of my hand. I’ve been thinking, as I do this, about parallels. The areas of each specimen that touched the image-scanner are in focus, while what was just a few inches back, away from the touch of the glass, is blurred. Likewise, passages that impress themselves upon me — whether through the sound of the prose, or the use of metaphor, or an observation I find close to my own experience — make their way to the pages of my notebook verbatim, while the other parts of the text are obscured, lost. They linger only as clouds of spoken words, hanging in the air.

Papers printed with images of animals flutter in Ann Hamilton: the common S E N S E. Image by the author.

“The sky shredded up, was torn by whirling birds.” (The Peregrine, p. 42)

The Henry invites museum-goers to take an image from the North galleries home with them. When someone pulls a sheet, the newsprint tears, breaking the hum of air and incantation. I feel a pang of loss. But I think, too, of the tearing sounds the birds in Baker’s book make as they fly and also of the tearing noise the tiercel makes as he pulls apart the bodies of his prey: woodpigeon, gull, lapwing, wigeon, partridge, fieldfare, moorhen, curlew, plover, duck. There are parallels here too, I think: ruptures in space, stalkers and spoils.

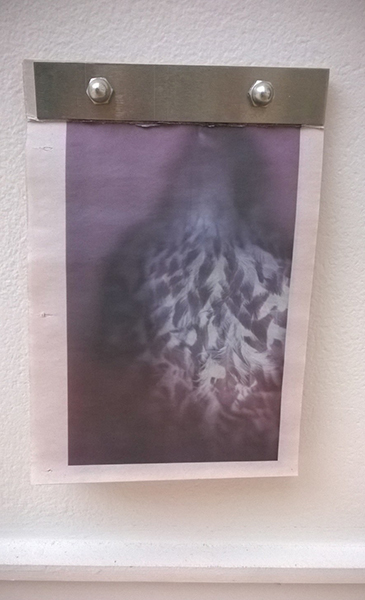

Torn and taken away, images consumed at the Henry Art Gallery. Image by the author.

“Woodpigeons, gluttonous innocents, rise like grey breath from every frozen plough.” (The Peregrine, p. 113)

My empathy shifts with what I address. The images in the North galleries are unlabeled, so mostly I guess at what I’m reading to, though I have sought out and found the one image of a peregrine.

I imagine myself giving counsel through Baker’s words. To a predator, I provide as a model the mostly successful hunting behavior of the falcon. “The short days of winter are lean, and you must eat,” I think. “Here, then, is how you stoop.” And to the woodpigeons and other prey: “This is how you avoid death.”

An image of a peregrine falcon in Ann Hamilton: the common S E N S E. Image by the author.

“I feel compelled to lie down in this numbing density of silence, to companion and comfort the dying…” (The Peregrine, p. 123)

Rebecca Solnit writes in her recent book, The Faraway Nearby, “A bestiary is buried in our language.” (p. 137) She refers to the great bear, Ursa Major, whose constellation gives name to the far north of the Arctic, to the Hog’s Head of the Cork-Kerry coast in Ireland, to the bashful human behavior we call sheepish, to the beelines we make in our directness, and to the things we crow about in our excitement. Our proximity to animals has fed our observations and fueled our imaginative language. “Language is humankind’s principal creation, a pale shadow of Creation, and one that needs to come back again and again to the nonhuman world to renew itself, to draw strength and color,” Solnit writes in an earlier, remarkable essay, “Noah’s Alphabet.” (As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art, p. 141)

But there is also a gulf that can never be bridged here in Hamilton’s show. The images and objects I address, already long dead, will never understand Baker’s words or even interpret the rise and fall of my voice.

I wrote, a few years ago, a brief article about Ann Hamilton’s floor piece at the Seattle Central Library. I had just read Michel de Certeau’s wonderful book The Practice of Everyday Life, and I was so taken with the quiet sedition of his ideas, so eager to apply his thinking about the expansive practice of readers to Hamilton’s piece, that I failed to acknowledge the loss that’s also inherent in the sculpture. Hamilton’s Floor of Babble is about the tactile pleasures of reading and the way worlds are made, opened up, with just a few words. But the sculpture is also, I’ve come to feel since I wrote that, about cacophony, the silent chatter of many voices at once. A single reader cannot make sense of all the many literary lines, all the different alphabets in Hamilton’s polyglot piece. The words are too much, too many, with one line pushed right up against the next. Incongruous, sometimes illegible, depending on our fluency, they leave us at a loss, lost in their vast accumulation.

Language and loss are also central to the common S E N S E. And so I read now in the galleries at the Henry with no hope of direct response. But in my reading, I attend and attend to. I give account and am accountable for. These are the bounties and burdens I gain in exchange for my small sacrifice of time.

Ann Hamilton: the common S E N S E is on view at the Henry Art Gallery through April 26, 2015. Learn more about how to participate as a reader/scribe during the run of the exhibition. Hamilton will be speaking on Monday, March 30th at Town Hall Seattle in an event presented by Seattle Arts & Lectures.

All quotations from The Peregrine are taken from a 2005 reprinting by the New York Review of Books, which features an excellent introductory essay by the British writer Robert Macfarlane.

Finally, an earlier, shorter version of this essay appeared on the Henry Art Gallery’s blog as “Chronicles of a Reader: the common S E N S E” on November 20, 2014. I republish and expand it here with the Henry’s permission.