Red Lodge, Montana, my father’s hometown, was a booming, raucous place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Following the discovery of coal in upper Rock Creek Valley in 1866, Finnish, Scottish, Welsh, and Italian immigrants – my great-grandfather and his family included – converged there, sustained by the mines that brought workers out of Red Lodge’s sheltered valley, onto the surrounding ridges, and then deep underground. In the decades before the arrival of these immigrant communities in south central Montana, a new understanding of time was emerging in the Western world. Scottish geologist Charles Lyell’s popular 1830 book, Principles of Geology, and other Victorian publications proposed that the Earth and the processes that had shaped it were millions of years old. Strict fidelity to Biblical time – Genesis’s account of creation, expulsion, and the purging flood that buoyed Noah, his family, and his ark of animals but spared no others – and corresponding belief in a six thousand-year-old world began to disintegrate. Charles Darwin read the first two volumes of Lyell’s book during his 1831-1836 research trip on the HMS Beagle. His theories of evolution, finally published in 1859 as On the Origin of Species, grew out of the new sense of geologic time Lyell and others had put forth.

At the same time as the sense of the past was widening, present and future were being remade. With industrialization and the advent of the factory line and its division of labor, time moved toward precision and synchronization. Nineteenth-century technologies like the telegraph and train were, what’s more, simultaneously remapping human relationships to space and, by extension, time. Distances previously traversable over the course of several days, for instance, were now traveled by train in a matter of hours. Though it was ships that brought immigrants from Europe to the United States, it was trains that most of the Montana transplants boarded to continue their travels west. By 1889, the Rocky Fork & Cooke City Railway, acquired the following year by the Northern Pacific Railway, arrived in Red Lodge. Given this background of temporal upheaval, how extraordinary, then, it would have been for one of these early twentieth-century Red Lodge miners to come upon the otherworldly remains of an ancient animal preserved in a coal seam, as stories my father heard from his mine-surveyor stepfather had it happening. According to his accounts, the miners were never able to carry the fossils out of the mine shafts. The bones crumbled in their hands as they tried to extract them from the rock.

Such an encounter must have lurched the discoverers backward in time, away from their dark and dirty work, and insisted, all at once, on their position in the strange present. The backward would have been, even if they had to guess at the particulars of some of it, to a period when a shallow sea covered what is now Montana and early turtles and reptiles swam its waters before the onset of the last ice age. And the present moment was their taxing, dangerous work to extract the sedimentary rock formed from the remains of this carbon-based life, now thousands of years dead and slowly transfigured into coal. They exhumed the fossil fuel to power the steam-engine trains that had brought them across the continent and were remaking the world around them.

In Ray Bradbury’s 1955 short story “The Dragon,” a pair of medieval knights attempts to charge a monstrous one-eyed dragon that turns out to be a roaring steam-engine train conducted by modern men. For the reader, as for the confused knights and conductors in Bradbury’s tale, the train represents a kind of temporal dissonance, a collision of two worlds. So, too, must have these ancient animals to the miners. They must have spoken, tacitly, of both a collapse and a clash of the ancient and the modern.

DECADES LATER AND back across a continent and ocean, Chris Marker’s 1962 film La Jetée takes place in a near-future Paris obliterated by war. A nameless hero fixates on an image of his past to travel back in time from this post-apocalyptic world. His captors are using him to try and salvage the ruined present. The image the protagonist chooses – indeed, it is still images that make up the entire film, aside from a fleeting few seconds of cinematic waking, blinking, and smiling – is a memory he cannot leave behind, a scene from before the outbreak of the war. As he recollects it, a beautiful woman waits on the pier of a Paris airport. All around her, planes, the skyward successors to the trains of the previous century, transgress space and time. The man and woman meet many times during these travels into the age of his childhood. The happiest occasion takes place at a natural history museum at Paris’s Jardin des Plantes. Here, as the film’s narrator says, “…they meet in a museum filled with ageless animals.” They walk its galleries, examining the taxidermied beasts and fowl that occupy its vitrines and plinths with glass eyes and animated gestures.

Five years after the release of Marker’s film, the French cultural theorist Michel Foucault spoke to a group of architects. In his talk “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” published years later in English, Foucault considers sites that contest and invert regular space. About the “other spaces” of the museum and the library he writes, “…[T]he idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity.” Other sites Foucault discusses are the Persian garden and the modern zoological garden. He calls these “universalizing heterotopias” for the way they function as microcosms, representing the whole world in a single place.

La Jetée’s natural history museum is both Foucault’s site of accumulated time and his universalizing heterotopia. As it does in the libraries and museums Foucault describes, time stretches for our cinematic protagonists, resurrecting the menagerie of once-deceased animals to bring them to the height of life. And there it stands still at an enchantingly protracted present as they blissfully explore, safe, like the animals they exclaim over, from its dangerous consequences before the spell is all too soon broken. Artist historian Carol Mavor has astutely noted in her book Black and Blue: The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans Soleil, and Hiroshima Mon Amour that even the sound of the film’s title conjures an elastic state of being. The place, Paris – with its famous gardens, museum, and airport – is definite, but the time is the extended imperfect tense: “là j’étais” (“there, I was”). The natural history museum is also, at the same time, Foucault’s microcosm. The man and woman marvel at the whole faunal world brought together in this thick condensation of display. Like Adam and Eve before the Biblical fall, they are innocents exploring the bounty of creation before the snake provoked sin and history began.

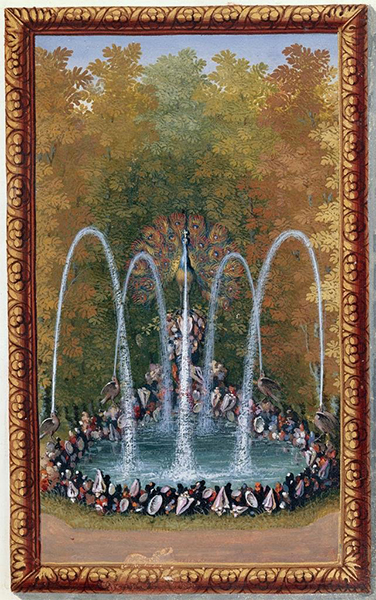

Mavor explores La Jetée as a kind of adult fairytale, where worlds dissolve into each other and sleep induces magical travel. One of the predecessors Mavor mentions for director Chris Marker is Charles Perrault, a seventeenth-century Frenchman and forerunner to the Brothers Grimm in establishing the genre of the fairytale. What she does not mention is that in addition to his publications, Perrault also advised King Louis XIV about the design of a labyrinth at the garden of Versailles just outside Paris. The labyrinth, constructed in the mid-1670s, featured both a hedge maze and a series of fountains representing characters from Aesop’s fables. Water spouted from the mouth of each sculptural animal, giving him the appearance of speech, and a caption and verse from the poet Isaac de Benserade supplemented the visual offering with didactic interpretation. As Perrault writes in his guidebook to the labyrinth, first published in 1675, “The Birds and the Beasts…are so beautifully designed that they seem alive, and engaged in the very actions which they represent.” Just, then, as La Jetée’s unnamed man and woman meet the taxidermied animals at the natural history museum in a suspended present, so, too, would Louis XIV’s young son, le Grand Dauphin, have come upon the labyrinth’s painted brass animals poised, always, at the same vivid moment. The fountains stood for a hundred years before Louis XVI, the great-great-great-grandson of Louis XIV, ordered the labyrinth destroyed in 1778.

“The Peacock and the Nightingale,” XVI (“Le Paon et le Rossignol”), folio 22 from Le Labyrinthe de Versailles by Charles Perrault, print by Sebastien Le Clerc, illuminated by Jacques Bailly. Image courtesy of Artstor.

LIKE MY FATHER, artist Mia Feuer spent her own childhood not among the ageless animals of Paris’s Jardin des Plantes or the ceaselessly babbling ones at the labyrinth of the Palace of Versailles but near sites of mineral extraction. She grew up in Winnipeg, and for her recent exhibition at Washington, D.C.’s, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Mia Feuer: An Unkindness, she conducted research in Alberta, north of Montana, at a site managed by Suncor Energy, the largest oil company in Canada.

There, at the Athabasca oil sands, Feuer was taken to a remarkable site. To mitigate the damage caused by the process of industrially mining crude bitumen – a process that involves removing the forest and top layer of earth and then diverting water from the nearby Athabasca River to create slurries from which the viscous oil could be gathered – Suncor undertook an extraordinary scheme, a staggering, sweeping set of actions. First they brought the top layer of soil back. They wanted to repopulate it with vegetation, but little would grow in the disturbed topsoil. One plant that would survive was wheat, which they introduced as a monoculture. The wheat attracted mice, whose population Suncor determined they needed to control to limit the spread of toxins. They thought to bring in a natural predator, ravens. But the ravens needed a place to roost. So the company imported birch trees, which they inserted into the ground top side down. The ravens roosted in the birches’ inverted root systems, surveying this colossal, altered terrain from above.

For An Unkindness, Feuer recreated a version of this disquieting landscape of attempt after attempt at impossible control. Dark feathers and a blackened oil drum perched on a light armature, filling the Corcoran’s classically coffered cream dome and evoking the group of ravens, the “unkindness” of the exhibition’s title. The artist does not exempt herself from her critical investigation of this place. Using materials derived from petroleum, Feuer is aware of her culpability in this strange ecology of sprawling, mostly unseen networks of production and consumption. She herself, then, is part of the systemic unkindness of brutal extraction and woefully misguided mitigation that the installation’s title also suggests. Below her suspended landscape, a 16-by-27-foot skating rink of black synthetic ice reflected shadows cast from above and invited a single museum-goer to don skates and enter its realm of quiet contemplation. The ice also harked back to a childhood memory of her father skating outside in the cold Canadian winter.

Below Mia Feuer’s installation An Unkindness. Image by the author.

But we are all skating on thin ice, Feuer implies, hurtling away from timeless fairytale romance and childhood enchantment, when we observed and identified with animals, and toward a future of vastly altered landscapes that we have remade in our ceaseless hunger to feed and grow the beast of the train and the technologies that have supplanted it. Those ancient remains of animals spoke to Montana miners of a mysteriously distant past and a contemporary world remade by industrialization. Feuer’s representations of ravens conjure a troubled, if mostly veiled, present and rush us forward to a looming future.

How will we answer back?