We’re coming to the end of daffodil season in Seattle. Everywhere I go, the flowers have been announcing spring, trumpeting forth the news with their proud center coronas and blaze of yellow.

It took me a long time to see something more than the daffodil’s bold color and message of seasonal change. These perennial flowers thrive from the moisture of fall and winter rains or snow, requiring little attention from the gardener, and they often grow in clusters, increasing from year to year without the aid of human intervention. As such, the hardy and social daffodil lacks the singular beauty of a treasured dahlia, for instance, whose summer bloom you attend with anticipation and remember with tenderness once it’s begun to shrivel and brown. The daffodil, in contrast, appeared to me prosaic, forgettable, no more than a champion of greater botanical glories to come.

Indeed, for the past several years, I have prized a more singular floral beauty. I pined, last spring, after a small, jewel-toned Dutch still life at the Seattle Art Museum’s exhibition European Masters: The Treasures of Seattle. It looked something like this stunning Bosschaert, with a lavish display of cut flowers that blossom, impossibly, all at once. Paintings like these show and preserve fictionalized moments of fleeting splendor. Michael Pollen places these Dutch masterpieces in history, writing in The Botany of Desire about the mad pursuit of floral beauty in seventeenth-century Amsterdam and the tulip cultivators and speculators who fueled the craze and made the flower a national obsession. I empathized with their preoccupation.

Ambrosius Bosschaert’s 1606 oil on copper painting Flowers in a Glass, now at the Cleavland Museum of Art. Bosschaert’s arrangement includes a cluster of daffodils in the upper left, but it is the large tulips around the bouquet’s top perimeter, silhouetted against the painting’s dark background, that are its crowning glory. Image courtesy of Artstor.

But a couple of lines from John Berger’s The Shape of a Pocket gave me pause. The English essayist writes, in passing, that nearly all paintings of flowers are pure spectacle. They offer dazzling displays of artistic showmanship representing plants themselves cultivated for their dazzling beauty. I thought of the humble daffodil I had so readily dismissed. I recalled its forward incline and world-curious corona. I thought to meet it with my own attention.

And so I happened upon what is, perhaps, the most famous poem by that famous Romantic man of letters, William Wordsworth. In the early years of the nineteenth century, Wordsworth penned his lyric poem about coming upon a vast field of daffodils. The verse, “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” praises the flowers for their “sprightly dance” and the jollity they elicit in the writer. The poem was inspired by a walk Wordsworth took with his sister Mary in England’s Lake District. But Wordsworth, as the poem’s title suggests, excludes Mary from the narrative, shaping the experience and his warm recollection of it as a meditation on the joys of solitary encounters with amicable nature.

It’s important, I think, that in the last stanza of the poem, Wordsworth himself, even if he just imagines it, bobs like the dancing daffodils surrounding him. He writes:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

In Wordsworth’s representation of the scene, you sense the poet’s Romantic fixation with his own observations and mind. But at the same time, he has also been a careful observer of the extant world; he inclines forward to relate to his environment. The daffodil, in turn, meets his gaze and buoys his spirits.

Southeast and some century and a half later, the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama presided over a different kind of congregation in a park outside the Venice Biennale. For her 1966 Narcissus Garden, Kusama massed a group of 1,500 polished, reflective balls. The title of her installation calls to mind the Greek myth of Narcissus, who, consumed with the beauty of his own reflection and unable pull himself away from the water that showed it, wasted away and died. Before Biennale officials voiced their objection to what they considered the performance’s trite commercialism and intervened to stop it, Kusama offered the balls for sale at the low price of 1,200 lire, or two dollars. Buyers could take them away, like cut flowers from a market, and gaze at their own likenesses. Grouped together, the field of balls also reflected the surrounding environment of the festival. In this way, the artist registered the Biennale’s see-and-be-seen atmosphere. Handing out copies of a statement by the British art critic Herbert Read about her own “original talent,” Kusama seems to include herself in her critique of self-focus and personal promotion.

A photograph of Yayoi Kusama’s 1966 performance/installation Narcissus Garden. Image courtesy of Yayoi Kusama: Look Now, See Forever.

But Narcissus is also the Latin name for the genus of bulbous flowers that includes the many varieties of daffodil. In my favorite photograph from Kusama’s performance, the smiling artist, clad in a traditional Japanese kimono and obi and cradling a ball in her left hand, bends forward to shake the hand of an older woman in a two-piece suit and heels. I imagine them a bit like the leaning daffodils and Wordsworth, the flowers’ bending dance partner. They attempt to relate.

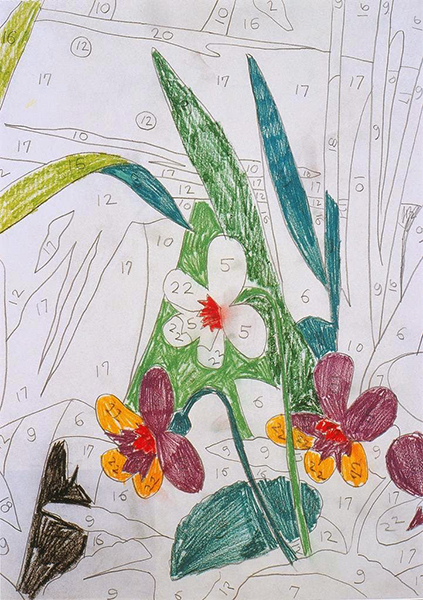

Four years before Kusama’s Narcissus Garden, Andy Warhol challenged the notion of a singular personal style that Kusama both perpetuated and critiqued with his Do It Yourself (Narcissus), one of a small series of Do It Yourself pieces he mapped from the paint-by-numbers diagrams Venus Paradise gave away in their sets of coloring pencils. Parts of the piece’s three center daffodils are filled in with color, but other areas and spaces surrounding the forward-leaning blooms are left blank, marked only with the number indicating the color they should take but never do. Warhol’s appropriation transforms the banal ready-made source image into a fine art reflection that comments on the mechanization, repetition, and excess of images in the twentieth century.

Andy Warhol’s 1962 Do It Yourself (Narcissus), graphite and colored crayon on paper. Image courtesy of Artstor.

The contemporary Seattle artist Matthew Offenbacher departs from Warhol’s sly treatment of banality and reaches for something much more earnest, I think, and in that way brings us back to Wordsworth and to my own new attention to the daffodil.

Seattle art critic Jen Graves wrote several years ago in response to a solo show by the artist, “There is something deeply embarrassing about Offenbacher’s paintings. They are embarrassed to be paintings — as if it were just an embarrassing thing to be a painting, so fancy and loaded and ambitious — and you are embarrassed to be looking at them, and in this way a connection is made…We have to wonder what this thing art is, and we have to justify our belief in it. And doing that — explaining a faith in something as insecure as art — is really hard and definitely embarrassing.”

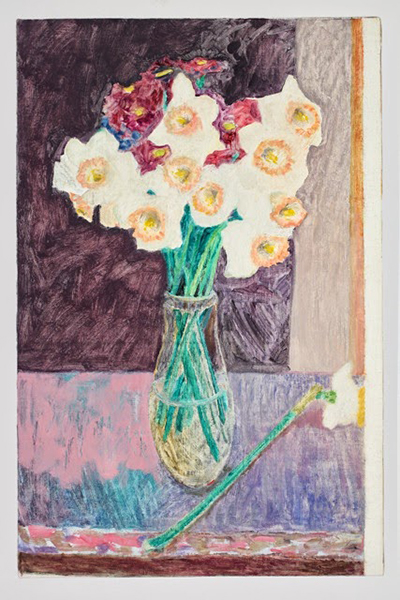

Matthew Offenbacher’s 2012 Daffodils, oil and acrylic. Image courtesy of Pulliam Fine Art Gallery in Portland.

Graves’s passage resonates with me. I felt it strongly when I saw Offenbacher’s lattice and grape column contribution to the Neddy Award exhibition at the Cornish College of Arts this past fall. It was so sweet, it cloyed. I could hardly look.

What I’ve come back to again and again in the artist’s visual work is his interest in the decorative and his attention to everyday domestic life. Offenbacher’s practice, I think, moves us away from John Berger’s spectacle and toward his idea of “collaboration,” even if it is an embarrassing one, among subject, painter, and viewer.

Offenbacher’s 2012 Daffodils, for instance, will hardly seduce you like a luscious Ambrosius Bosschaert. It is too mundane in its choice of subject, too ingenuous in its execution to constitute anything like spectacle.

But come early springtime, people everywhere, hungry for the end of another grey winter, cut sunny daffodils from their yards and bring them inside to place in glass vases and perch on tabletops and window sills. Offenbacher, in his representation, asks us to look back at so ordinary a sight.