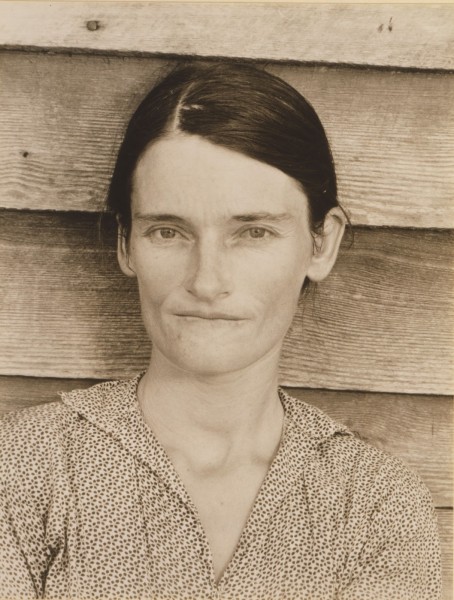

Walker Evans, Allie Mae Burroughs, Hale County, Alabama, gelatin silver print, 1936. Image courtesy of Bank of America.

In November, Bank of America launched a virtual exhibition, sometimes accessible from the homepage of its website, called Bearing Witness: Documentary Photography of the 1930s. Composed of works from the Bank of America Collection, the show highlights American photography made during the Great Depression. The images present both rural and urban scenes. Figures, many of them still familiar to contemporary viewers, are often shown as characters of tenacity and grit, folks holding on while dust storms and economic hardship ravaged the United States.

Bearing Witness is Bank of America’s first entirely virtual display of art. The exhibition also serves as a companion piece to documentary filmmaker Ken Burns’s PBS program The Dust Bowl, the latest in a series of Burns documentaries that Bank of America has financed. Bank of America also funds New York’s Carnegie Hall, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and grants to nonprofit museums to conserve and clean paintings, works on paper, and decorative objects. It also supports free visits to museums and cultural institutions for Bank of America and Merrill Lynch cardholders on select days. In addition, it has curated a number of art exhibitions for a program called Art in our Communities®, which, since its launch in 2008, has loaned shows made up of works in Bank of America’s collection to museums around the world. Through this program, museums are able to bring in revenue generated by admissions fees to these borrowed exhibitions but forgo the expenses of assembling works from various collections as well as the cost of art historical scholarship and writing.

These shows are not, by any means, the work of detached aesthetes. Many take on difficult themes, including environmental sustainability, gentrification, political activism, racial identity, and the social construction of gender. But I’m troubled by the anonymity of the scholarship and curatorial work that produced them. Of the twenty exhibitions featured on their website, only four mention association with nonprofit museums (the National Museum of Mexican Art; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the National Museum of Women in the Arts) or an independent curator (Deborah Willis).

Displayed alongside museum collections and loans, Bank of America’s works stand to gain value. In promoting its generous exhibitions program, Bank of American is thus also growing its own assets. What’s more, corporate collections do not bear the same burden of responsibility that accredited museums do to maintain a collection and serve a public. For nonprofit museums, the decision to deaccession a work of art, for example, is supposed to be made with the express purpose of strengthening the quality and distinguishing the identity of the institution’s collection, thereby enhancing its ability to fulfill its mission. All proceeds from the sale must, according to the Association of Art Museum Directors, be used to finance the acquisition of other works of art; the money cannot go to support general operating costs or to increase the institution’s endowment. Bank of America and other for-profit corporations like it are under no such obligations. Should money get tight, corporations can choose to sell off their art holdings, as institutions like Lehman Brothers and British American Tobacco have done in recent years. With their provenance and display history at various museums, the works in Bank of America’s collection would be in a position to fetch a great deal of money.

Examining the online exhibition Bearing Witness, what’s striking is that the show’s writing makes no pretense about hiding the federal funding that financed the creation of this body of photographic work. Instead, the text panels openly celebrate the era’s championing of art as a civic good worthy of taxpayer dollars. At the beginning of the section on the Works Progress Administration and the Federal Art Project, the unnamed scholar(s) responsible for the show’s text writes,

Despite this open acknowledgement of the political context behind the creation of the photographs featured in Bearing Witness, I am ruffled by the subject of this show. I take exception to Bank of America laying claim to an American cultural heritage that was directly supported by the federal government. I am uneasy about a contemporary system that has transferred the responsibilities of elected government, which has historically supported artists and the museums that preserve and present their work, to corporations ultimately responsible to only their shareholders. However admirable its civic-mindedness, Bank of America is motivated foremost by profit margins, not its social largesse.

Indeed, if Bank of America has earned a reputation for generosity in the arts in recent years, its has, at the same time, drawn scrutiny for its unscrupulous financial dealings. In a late 2010 settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Bank of America agreed to pay 137 million dollars to settle charges of corrupt behavior in municipal markets. A little over a month ago, a federal prosecutor filed suit against Bank of America, alleging that its toxic mortgages, assumed when it acquired Countrywide Financial in 2008, the same year it inaugurated Art in our Communities®, have cost American taxpayers over one billion dollars. And Bank of America may now be improving its reputation with housing counselors, but the increasing tranparency of its foreclosure process for homeowners is, in large part, mandated by a settlement with states. We must not allow philanthropy to assuage justifiable public ire over the Bank’s disreputable dealings. Bank of America is more than the polished public image its arts programs present. And to create an exhibition about economic hardship when they themselves are partially responsible for the worst recession in the Unities States since the 1930s exploits these images and demonstrates a slippery gall that deeply offends.

The arts need support, to be sure. Artists are communicators who help us make connections among disparate subjects, sharpen our analytical prowess, see beauty in places we might otherwise overlook, and draw us out beyond our own individual lives. Many have even made and are continuing to create art that pulls back the bed sheets to show what strange and often unsuitable bedfellows corporations and art institutions make.

Last month, for instance, members of the Reclaim Shakespeare Company gathered, uninvited, in the Great Court at the British Museum to perform altered scenes from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. The performances, which included the chant “double, double, oil is trouble; tar sands burn as greenwash bubbles,” drew attention to British Petroleum’s corporate sponsorship of the exhibition Shakespeare: Staging the World, dramatizing the corporation’s flawed environmental record and its cozy relationship with British cultural institutions. These theatrical protest were staged in the same week that the oil giant accepted criminal responsibility for the 2010 Deepwater Horizon rig explosion and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. They also come on the heels of a July protest in which Liberate Tate activists brought a wind turbine blade into the Tate Modern Turbine Hall gallery to protest BP’s sponsorship of the museum.

Before this year’s slew of British protests, German-born artist Hans Haacke had already made a career of institutional critique, creating work that calls attention to the increasingly close alignment of corporations and museums. For a 1975 installation called On Social Grease at New York’s John Webber Gallery, Haacke made six magnesium plates mounted on aluminum. The plates resemble plaques that bear the names of charitable donors in many museums, but the words tell a different story. Each plaque displays photoengraved quotations excerpted from public remarks given by figures prominent for both their business standing and acumen as well as their support of and involvement with the arts. In the plate below, David Rockefeller, then Chief Executive Officer of the Chase Manhattan Bank Corporation and Vice Chairman of the Museum of Modern Art, discusses business’s involvement with the arts as a sound investment. Attaching a corporation’s name to a museum exhibition or philharmonic season can build public approval that translates into what Rockefeller calls “tangible benefits,” such as revenue.

Hans Haacke, On Social Grease (quotation from David Rockefeller’s 1966 “Culture and the Corporation’s Support of the Arts” speech to the National Industrial Conference Board, one of six panels), 1975. Image courtesy of the Tate Gallery; photograph by Walter Russell.

Like the Reclaim Shakespeare Company, Liberate Tate, and Hans Haacke, I want to register my disquiet about what I see as the fraught relationship between companies, such as Bank of America, and nonprofit arts organizations. I want to keep alert to the concessions to opacity, self-interest, and contradiction I think are so often at play in for-profit corporations’ involvement in the arts.

I bear witness to my own time.