Last month at the Reykjavik Art Museum in Iceland, I saw exhibitions devoted to the careers of two Spanish artists: Antoni Tàpies and Santiago Sierra. Divided by two generations and chosen mediums and subjects, Tàpies and Sierra nonetheless share a basic preoccupation with human bodies.

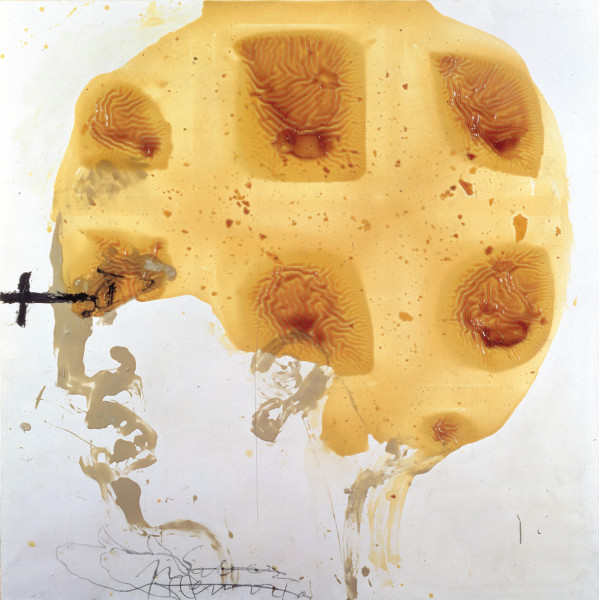

Before he passed away earlier this year, Tàpies built up layers of material — paint, sand, resin, dirt, and powdered marble — on canvas and wood. In one work from the show, areas of resin appear like dessicated pools of sweet, sticky honey. They wrinkle and fold like the ins and outs of complex internal organs or skin that has aged in the sun. Shown in the space above and behind a face in profile, they look like areas of brain activity, or perhaps disease.

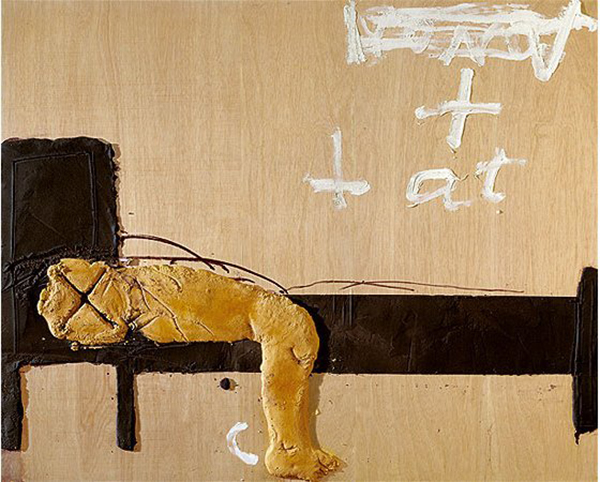

Tàpies played with these layers and dimensionality, flattening body parts so that they draw parallel to painterly surface, as, for instance, a leg bends alongside a bed, or a hand presses forward into the flat surface of the picture plane. He built up material, but he also subtracted, scrawling into work with his signature “t” or cross shape. Just as much as the recognizable extremities and heads and hair testify to the artist’s extended exploration of the body in painting, these persistent marks give witness to the unflagging presence of the Catalan artist’s own hand on and in his large body of work.

Santiago Sierra, Hooded woman seated facing the wall, originally performed in the Spanish pavilion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, re-enacted at New York’s Lisson Gallery in 2010. Image courtesy of Metropolis M.

Where Antoni Tàpies amassed and took away to create visceral and sometimes fragile works, Santiago Sierra organizes and stages to expose social inequities and the culpability of institutions that sustain them. His works often employ marginalized populations to perform menial tasks, for which Sierra remunerates them at the going rate, depending on the location. The performances are documented with video, mostly black and white, which is how they were re-presented in Reykjavik.

For me, the most compelling of Sierra’s works are the ones that use the gallery or museum to frame labor. A hooded woman sits in a gallery space for a few hours, but she must turn away from displayed objects and other viewers to look only at a corner of the room. In another piece, men bear the weight of a beam connected at its other end to a gallery wall. In a third, figures with arms stretched forward and above their heads support a white wall that inclines toward them. These pieces call to mind the work of New York City-based feminist artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, who, in performances from 1973, publicly cleaned Hartford, Connecticut’s Wadsworth Atheneum to show the labor that underwrites the intellectual activity we associate with cultural organizations like libraries and museums. The beam and wall in Sierra’s work bring to mind sculptures by the minimalist artists Carl Andre and Richard Serra. But instead of encountering these stand-alone sculptural/architectural objects in time and space like we do with work of the two American artists, in Sierra’s pieces we become implicated in a narrative about the difficult, bodily labor it takes to support the presence of objects in high-culture spaces.

Santiago Sierra, Muro de una galeria arrancado, inclinado a 60 grados del suelo y sostenido por 5 personas, México D.F., 2000. Image courtesy of sdelbiombo.

Reflecting back on the shows, I am struck, especially, by how the Reykjavik Art Museum presented Sierra’s work in the introductory text to the exhibition. Iceland, they reminded viewers, has undergone recent fiscal and political crisis. Perhaps an artist like Sierra, they asserted, can help museum-goers reflect on those difficult experiences and examine how their own bodies, lives, and work intersect with the larger financial, political, and cultural forces at play.