Whatever the weather, spring officially begins today, March 20th. Heeding the impending day, I hastened to finish Adam Gopnik’s most recent book, Winter: Five Windows on the Season, before the vernal equinox heralded the new season and winter melted away. In the last months, Gopnik has been a constant companion. I was charmed by his 2001 Canadian/American in Paris memoir, Paris to the Moon, then keenly followed his routines and ruminations in the 2006 Through the Children’s Gate: A Home in New York. The five chapters of his latest book were first delivered over Canadian radio as the annual Massey Lectures. Collected together now, these essays are at once more colloquial and less explicitly imprinted by events in Gopnik’s personal life, which in previous publications have provided fodder for thoughtful reflection just as French bureaucracy, Alice Waters’s cooking, and Brooklyn’s population of feral parrots did. In Winter, Gopnik is an inquisitive and evocative cultural historian, deftly weaving together histories of visual and commercial art, literature, music, polar exploration, Christmas celebration, snow and ice sports, urban development, and memory to contend that our warmth for the season of cold is a mark of a modern sensibility that has taken shape in the last two hundred years.

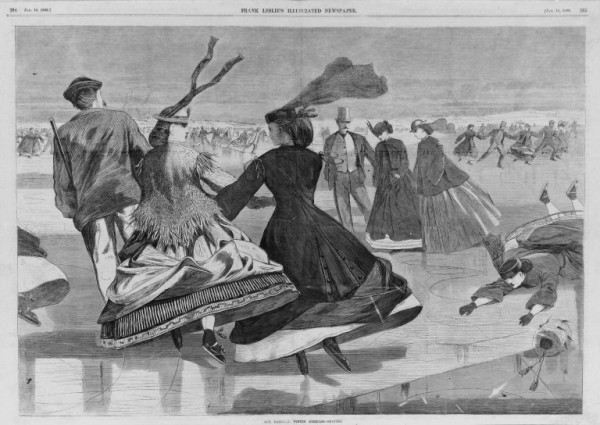

Winslow Homer, Our National Winter Exercise — Skating, wood engraving, 1866. Image courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Skating is one subject Gopnik takes up in his fourth chapter, “Recreational Winter: The Season at Speed.” With his usual aplomb, Gopnik writes a caption for an 1866 image of the sport by American artist Wislow Homer. “…Homer saw New York’s exciting new Central Park as a lek for flirtation, fashion competition — see those flying ribbons! — and unimpeded sexual display.”

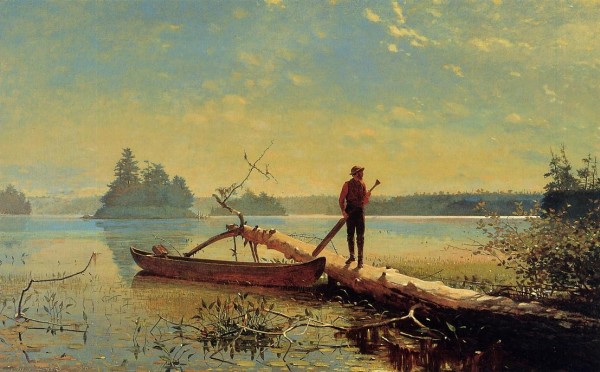

Winslow Homer, An Adirondack Lake, oil on canvas, 1870, part of the Henry Art Gallery’s permanent collection. Image courtesy of the Henry.

I thought of Gopnik and those whipping ribbons when I was in front of another Homer work a few days later. Homer’s An Adirondack Lake of 1870 is part of curator Sara Krajewski’s two-work exhibition Pollen and Paint: Laib, Homer, and the Natural World at the Henry Art Gallery. Both Homers are about skillful management of the body. But where Our National Winter Exercise intimates a winter’s tale of urban sociability and elegant dress, An Adirondack Lake is all sun-kissed quiet concentration and rural solitude. In this latter image, a backwoodsman trapper or trapping guide turns to look at something outside the picture’s frame. As he balances on a bark-stripped log jutting out into the lake, he brings his paddle across his body, echoing a delicately gnarled branch projecting from the narrow end of the tree trunk.

Homer intended these two pieces for very different kinds of consumption. Our National Winter Exercise was first published in the magazine Harper’s Weekly, a kind of forerunner of the New Yorker, where it vied with words and other images for attention. Just as its expert skaters move past at swift speed, Homer’s print is meant for rapid intake. The large scale of his later oil painting, alternatively, demands singular, focused attention. The Henry presents An Adirondack Lake alone in a north gallery room, amplifying its specialness. The museum also invites extended contemplation of the painting with the bench it places before it. I inspected the piece closely, stepped back to look at a distance, and then sat in front of it for a long time.

Wolfgang Laib, Pollen from Hazelnut, hazelnut pollen, 1995-1996, in the permanent collection at the Henry Art Gallery. Image courtesy of the Henry.

Across the barrel-vaulted corridor in the room opposite, sitting is not an option. Viewers stand, one at a time, in a little lookout space demarcated with short plexiglass walls. Here, they take in Wolfgang Laib’s palpably close floor piece, a rectangular yellow monochrome called Pollen from Hazelnut. At its edges, the bright rectangle becomes fainter, disappearing into the flat grey floor. But everywhere else, the concentration of material is dense. Spotting patterns in its expanse feels like tracing fault lines in the earth. Meanwhile, the buzz of the air vents in the gallery sounds like industrious but invisible honeybees gathering above this cloud of color. As the title suggests, Laib created the piece from spring-time deposits of pollen he gathered in fields near his home in southern Germany. The Henry has removed curtains from the skylights in both the Laib and Homer galleries. When clouds move to cover the sun, and the rooms darken, both works seem to glow.

Adam Gopnik closes Winter: Five Windows on the Season with some beautiful passages, one of which I reproduce here. It is about the color yellow, so essential to both the Homer and Laib pieces at the Henry, and about our acts of naming, collecting, and relating to the natural world, which both artists do so persuasively.

“I recall once when I got word that my best friend was dying and I happened to pass a paint store where all the shades of yellow were laid out and named, quite cleverly and precisely — lemon zest and buttercup and canary, each shade given a personality — and I thought, This is all a lie. The spectrum of light is as indifferent as the rest of the universe. ‘Buttercup’ and ‘lemon zest’ were not labels but just lies, hopeful names given to arbitrary swatches in a physical phenomenon of light, which is not only indifferent to our existence but without any kind of neat internal structure at all, with no more charm or colour than the indifferent hum of a radio on the wrong station.

“There are moments when we experience winter as, in effect, the universe experiences it: loveless and emotionless and just there, an endless cycling of physical law that is not just indifferent to our feelings but in some sense so arbitrary that it doesn’t even have the quality of being elemental…We live in a cold world.

“But instead we give the coldness names, we write it poetry, we play it music, we experience it as a personality — and this is and remains the act of humanism. Armed with that hope, we see not waste and cold but light and mystery and wonder and something called January. We see not stilled atoms in a senseless world. We see winter.” (Winter: Five Windows on the Season, pages 210-211)

And now we see and welcome spring.

Pollen and Paint: Laib, Homer, and the Natural World is up at the Henry through May 6th. Adam Gopnik’s Winter: Five Windows on the Season is available at Third Place Books and other Seattle bookstores.