The cover of Sylvia Lavin’s 2011 book, Kissing Architecture. Image courtesy of Princeton University Press.

On this day of love, relationship advice from UCLA architectural historian and theorist Sylvia Lavin to architecture and contemporary art: “‘To be one with’ may make a nice romantic fantasy, but ‘to be two with’ makes more profound politics. And possibly more gratifying as well. When kissing and enmeshed, architecture is surprised into responding, made aware of the added value of another’s mouth that seeks neither nourishment nor reproduction. Kissing requires not only that architecture receive the kiss but that it participate in return: that it kiss back.” (Kissing Architecture, page 110)

Kissing Architecture, the first book in a new series called POINT: Essays on Architecture, is not for the chaste. Lavin writes for an audience already intimate with recent and contemporary architecture, art, and theory. The rewards of her slim book are, however, many as she jumps nimbly from artist Andy Warhol to design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro to art critic Clement Greenberg to French philosopher Gilles Deluze in considering what she calls “superarchitecture,” a new kind of cultural project in which architecture is coupled with another medium to create time-sensitive environments. Kissing Architecture is itself a union of disparate and engaging materials. Bright pink, fabric-wrapped soft covers open to slick, glossy pages. Sited at the intersection of art and architecture, Lavin’s writing can be connected to the scholarship of figures like Giuliana Bruno and Beatriz Colomina. Considering a variety of projects, Lavin, throughout the book, celebrates the value of vivid experience rather than just visual perception.

She focuses especially on the smart pairing of architecture and video installations and on architects and artists engaging with the architectural façade, or surface, in sculptural ways. Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out receives a lengthy discussion. This 2008-2009 installation aimed at, as Rist describes it, melting in and kissing Yoshio Taniguchi’s 2004 renovation of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Through a combination of video projections, sound, carpet, and furniture, Rist brought sensuality and femininity to a space that has, for many other artists, proven cold and dwarfing.

Pipilotti Rist’s Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2008. Image courtesy of the New York Times.

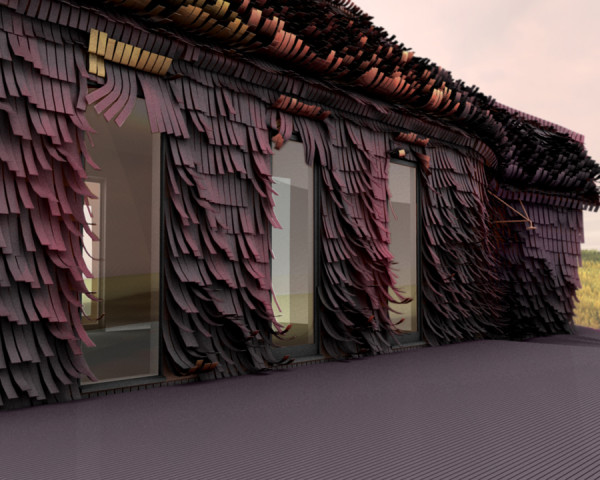

While Rist animates interiors, Doug Aitken often projects films on the exteriors of buildings. His soon to be finished Lighthouse in southeastern New York, with Allied Works, will marry external building surfaces with video of the surrounding environment filmed in the different seasons. Jason Payne, lead designer for a renovation project called Raspberry Fields in rural Utah, has also played with the idea of the façade, derived from French to the refer to a building’s “face.” On the side of the renovated building that faces toward town, conventional shingles supply the former schoolhouse’s public face. On the more private and exposed side, Payne has designed shingles that, like leaves, respond to whipping winds, curling up to reveal orange and purple undersides that reference the site’s nearby raspberry plants. Lavin writes absorbingly, “The old little schoolhouse is still visible inside its strange fur coat, but it is no longer cold and alone, a stalwart piece of architecture against the world, standing in defiant self-sufficiency, in need of no one and nothing. And it has been neither fetishized, nor castigated: instead, it has received a warm embrace in which it…blooms.” (Kissing Architecture, page 108)

Concluding her short volume, Lavin invokes the importance of politics and ethics in the entwining of art and architecture. But if sociopolitical motivations underlie her project, Lavin does not wear a heavy heart on her sleeve. She smartly keeps her writing light, playfully drawing out her extended analogy of kissing throughout the book’s four sections. If this is your first rendezvous with Lavin, I hope that she will soon become one of your steadies. In addition to her earlier publications, she has a forthcoming title, The Flash in the Pan and Other Forms of Architectural Contemporaneity.

May you fall madly in love.