It was a wild and windy morning when my partner and I arrived at the Tracy House in Normandy Park, Washington, a few weeks ago. In the previous days, Seattle had been buried under inches of snow, and we had been housebound, venturing out only for sledding and short walks. Making our way south of the city through the melting snow, we arrived at the Tracy House and exchanged our hundred year-old Craftsman for the sophistication of Frank Lloyd Wright’s late work.

Sited on a dramatic property that faces out to the Puget Sound and Olympic Mountains, the Tracy House is one of Wright’s Usonian Automatics. These are affordable American houses built in the last decade of the architect’s life (1867-1959), composed of concrete blocks held together by steel mesh, reinforcing bars, and cement grout. There had been earlier block houses in Wright’s career, including the Los Angeles Ennis House, which memorably serves as the home of protagonist Rick Deckard in the excellent 1982 science fiction film Blade Runner. For the Usonian Automatics, Wright simplified the design, reducing walls to the thickness of one block and eliminating wood beam and panel ceilings in favor of coffered ceilings of concrete blocks. He hoped that one day the blocks could be made by machines, purchased at building supply yards by people constructing their own homes, and assembled according to one of several preconceived and commercially available plans. Mass production, however, never took off. Elizabeth and Bill Tracy, who commissioned their house in the early 1950s, worked for about a year with steel forms to cast the house’s seventeen hundred concrete blocks from eleven different block designs. Wright never visited the property, crafting his design from detailed site plans instead. At the request of Mr. Tracy, trained as an architect and structural engineer, Wright designed a deeper overhang on the west side of the house and strengthened the structure with additional steel reinforcing and roof insulation. After the house was finished in 1955, Elizabeth dutifully waxed the red concrete floor tiles throughout the property. Only at age 90 did she give up regularly caring for the exterior terrace tiles.

Seattle Met Magazine recently named the Tracy House one of Seattle’s ten best homes, and we visited as executer Larry Woodin held court. What was billed as an EcoHome Foundation tour was more like an open house. At first I wished that I had read more about the house before we came. Our experience here had not been rigorously crafted, as is done at Wright’s chef-d’oeuvre, Fallingwater, in rural Pennsylvania. There, tour group sizes, schedules, and routes are precise and firmly established. At the Tracy House, we were largely left to our own devices, walking and observing as we liked. Mild displeasure gave way to the gift of discovery. As we moved through the property’s open plan, we remarked upon its Wrightian hallmarks: cascading steps that marry the house to the natural topography of the site, broad cornices that give the house a low-slung horizontality and sense of shelter, built-in seating and clearstory windows, an integral fireplace that makes the hearth the heart of the home, and varying ceiling heights that indicate intended use and give each space its own distinct psychology.

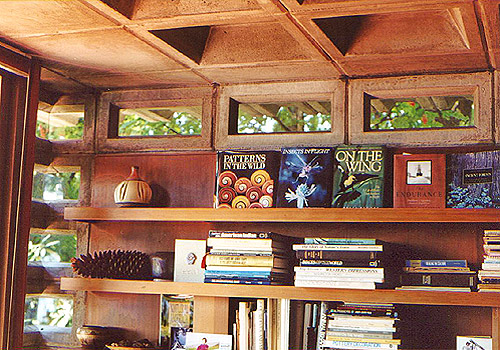

The living room bookshelves, clearstory and corner windows, and coffered ceiling. Image courtesy of Douglas Steiner.

A house plant climbs the concrete blocks and inset lighting in the dining room. Image courtesy of Douglas Steiner.

The mitered glass corner windows and the vanity’s exposed light-bulbs in the bathroom. Image courtesy of Redfin.

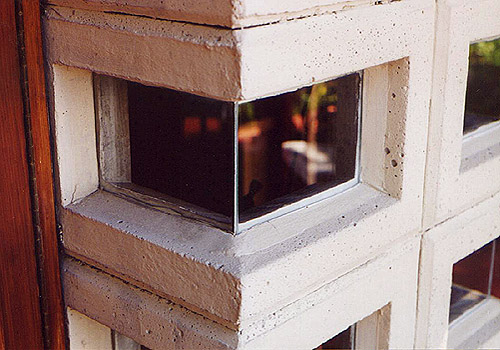

An exterior view of the mitered glass and perforated concrete block corner windows. Image courtesy of Douglas Steiner.

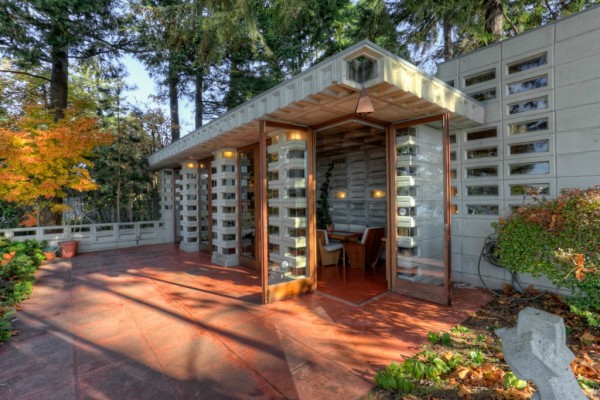

As we ambled and discussed, I became fixated on corners and how often Wright skillfully effaced them. At either end of an interior wall that screens the dining room from the fireplace and a hidden laundry and storage room, he used a distinct corner block. In place of adjoining sides that meet at a right angle to create a sharp corner, he beveled the blocks’ edges, creating a series of small voids that increase visual access and encourage visitors to move around from the living room to the dining room and again from the dining room to the kitchen and laundry room. In the living room and bathroom, he employed mitered glass and perforated concrete block corners to make the spaces seem bigger and to bring natural light into the interior. This increased space and light heightens the unity of the interior and exterior spaces, which Wright has already joined through his repetition of materials inside and out. Perhaps his cleverest obliteration of a corner is at the French doors onto the back terrace. The corner doors open out, entirely freeing the dining room to the outside. He reiterates his removal of the corner here by taking out the corner block of the overhanging cornice above.

Frank Lloyd Wright exploded the corner at the back of the Tracy house, collapsing inside and outside. Image courtesy of Redfin.

Wright was not the first to destroy the architectural corner. As I learned in a class at the University of Washington on the De Stijl movement and its impact on the Bauhaus School in Germany, the Dutch furniture designer and architect Gerrit Rietveld had experimented with the effect some thirty years earlier for his Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht (1924). On the east side of the house, an upper floor corner window seems to lose its corner when its perpendicular panels are swung open, a mark of Rietveld’s playfulness with structure and how he successfully achieved his client’s desire to be closer to the light, sun, wind, rain, and changes in nature. Positioned close by, Rietveld’s asymmetrical and planar 1923 Berlin Chair seems to sit in for the missing corner.

The Tracys are now deceased, and their house is on the market. Like Truus Schröder-Schräder and Charles and Ray Eameses, Elizabeth and Bill enjoyed decades in their home. Architecture, indeed, is often a medium of time and repeated movement. Based upon my own short morning in Normandy Park, I can tell you that the Tracy house, like all good art, rewards careful study. Beyond the play with corners, other design delights, I am sure, reveal themselves over time. I can only imagine the quiet contentment the Tracys’ house afforded them as they watched the seasons change through each window and the sun sink behind the Olympic mountains in the evenings, spilling onto and then disappearing from their dining room table.