In the late winter of 1928, the Seattle Theatre, now the Paramount, opened its doors for the first time. As recounted on its website, it showcased an impressive lobby outfitted with “French baroque plaster moldings, gold-leaf encrusted wall medallions, rich paint colors, beaded chandeliers, and lacy ironwork.” It was, and now is again since its 1990s restoration, an opulent people’s palace modeled after a regal predecessor, Louis XIV’s Versailles. Inside, the auditorium seats just shy of four thousand patrons. On a typical evening in the late 1920s, they would have assembled to take in a brief orchestral excerpt, a newsreel, a performance on the Mighty Wurlitzer Organ, an elaborate vaudeville show, and, finally, a silent film accompanied by organ music.

The balcony of Seattle’s Paramount Theatre, 2007. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; photograph by Joe Mabel.

In the mid-1920s, German cultural critic and film theorist Siegfried Kracauer wrote about how the multi-sensory offerings at Berlin’s picture palaces dressed up film as theatre and deprived the two-dimensional medium of realizing its true essence. “This total artwork of effects,” he argues, “assaults every one of the senses using every possible means. Spotlights shower their beams into the auditorium, sprinkling across festive drapes or rippling through colorful growth-like glass fixtures. The orchestra asserts itself as an independent power, its acoustic production buttressed by the responsory of the lighting. Every emotion is accorded its own acoustic expression, its color value in the spectrum – an optical and acoustic kaleidoscope which provides the setting for the physical activity on stage, pantomime and ballet. Until finally the white surface descends and the events of the three-dimensional stage imperceptibly blend into two-dimensional illusions. Alongside the legitimate revues, such shows are the leading attraction in Berlin today. They raise distraction to the level of culture…”

I don’t pretend to equate live music with cinema. But at the Paramount earlier this fall listening to the band Fleet Foxes play “Montezuma,” the first track from their most recent album, I noticed how the opulent grandeur of the theatre, the flashing spotlights, and even the band’s two-dimensional video display, synchronized to complement the music, faded away. I was left with the sound, the astonishing sense of great space, and the shared rapture of the audience, who, gathered like an expectant congregation, hung on lead singer Robin Pecknold’s every sung word. Far from distracted, we shared with the band a powerfully attuned concentration.

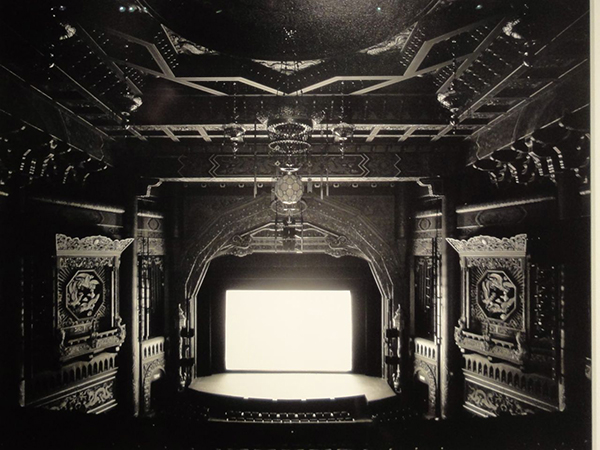

Later, the theatre photographs of Hiroshi Sugimoto came to mind. I thought especially of his Fifth Avenue Theatre, Seattle at the Seattle Art Museum. Much like the lyrics of “Montezuma,” which jump back and forth from past to present, Sugimoto’s theatre series is a meditation on time. Defying our common understanding of a photograph as an instant arrested — what twentieth-century French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment” when the photographer captures a formally compelling image through a combination of intuition and spontaneity — Sugimoto uses the full duration of a film screening as the exposure time. In his resulting photographs, the entirety of the film, itself a rhythmic splicing together of many discrete still images, is distilled as a single, glowing rectangle. Light from the screen washes over the immobile architecture that frames it, and time is suspended.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Fifth Avenue Theatre, Seattle, gelatin silver photograph, 1997. Image courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum.

Sugimoto’s Fifth Avenue Theatre, Seattle is in the permanent collection of the Seattle Art Museum. Free tours of the Paramount are offered at 10 a.m. on the first Saturday of each month. On Monday evenings during the end of January and the beginning of February, the Paramount will show Academy Award-winning silent films, accompanied by its famous Mighty Wurlitzer Theater Pipe Organ.