One of the poster designs for Gary Hustwit’s film Urbanized, by the graphic design studio Build, 2011. Image courtesy of Fastcodesign.

For these past weeks, as I traveled from Seattle to Omaha and then Baltimore, I’ve been mulling over a number of issues. They have coalesced for me on what I see as a common ground. Let me explain.

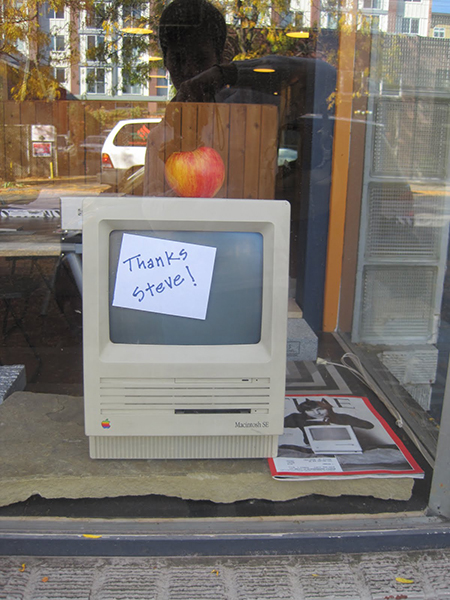

Back in August, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney, provoked by a vocally assertive contingent over tax and entitlement programs questions at the Iowa State Fair, retorted with the now famous line “Corporations are people, my friend.” Romney’s words took on new resonance in the wake of Apple founder Steve Jobs’s recent death. Rarely has a company been so identified with the creative vision and branding savvy of a single person.

An homage to Steve Jobs at a storefront in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood, 2011. Image by the author.

Romney’s words have, of course, also become fodder for protesters associated with the Occupy Wall Street and other Occupy movements across the country. A recent and very thoughtful New York Times article by architecture critic Michael Kimmelman about the New York City protest considers how the Wall Street occupiers are creating a new kind of city and social contract, “an architecture of consciousness.” The same day as Kimmelman’s “In Protest, the Power of Place” article ran, James B. Stewart’s piece “A Genius of the Storefront, Too,” appeared in the New York Times. Stewart’s article outlines Steve Jobs’s longtime collaboration with the architectural firm Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, labeling the resulting Apple architecture “sleek, transparent, inviting, technologically advanced – and expensive. In many ways,” Stewart continues, “the retail architecture is simply the largest box in which an Apple product is wrapped, and Mr. Jobs was famously attentive to every detail in an Apple product’s presentation and customer experience.” Like I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid that draws visitors underground to the Louvre, the Fifth Avenue Apple cube has been successful at enticing would-be buyers into the retail space below. But as Mr. Kimmelman points out in his own article, what now passes for public space is often actually corporately owned, its landowners compelled by the bottom line (if also the production of aesthetically pleasing products that place technological access within the hands of those who can afford it) and not necessarily the larger civic good. Kimmelman calls this disappearance a “bankruptcy of…public space,” a shift away from “an arena of public expression and public assembly…to a commercial sop.”

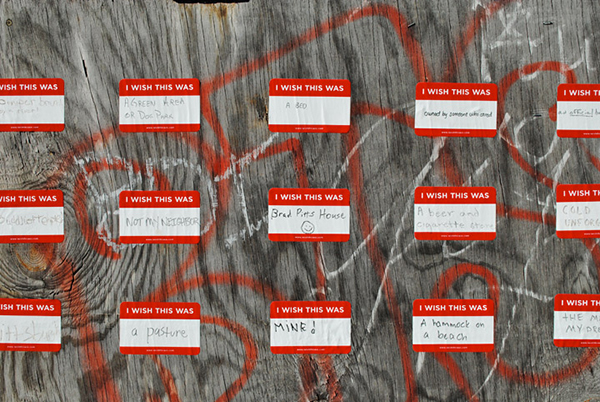

How people make and interact in spaces has been very much in the public eye in recent weeks. The new film Urbanized, the third and final installment of director Gary Hustwit’s design documentary trilogy, takes us to cities across the world, where designers work to find creative solutions to urban issues like affordable housing, transportation, and safety. One of the cities Hustwit profiles is New Orleans, battered and soul-searching after Hurricane Katrina. There, artist Candy Chang started a project last autumn called “I Wish This Was: Civic Input On-Site.” Passers-by are invited to fill in blank vinyl stickers Chang has placed along vacant storefronts, sharing their hopes for the empty lot and for their community. Chang is especially interested in how neighbors can connect to one another in an age in which it is often easier to communicate virtually, thanks to personal computer and mobile device innovations pioneered by Jobs and others.

What I start to take away from this convergence of news stories, people, and ideas is that we can’t know solutions, much less identify problems, without the space for dialogue. Part of the power of place – be it the Iowa State Fair, Zuccotti Park, the streets of New Orleans, or even virtual spaces like this forum – is granting us the space to gather, consider, and converse together.