A few weeks back, I heard a geographer speak as part of a panel about women and the urban environment. She said she’s often asked about the nature of her discipline. In response, she said she talks about thinking about space as structuring human relationships. She talks about how the city has a geography, home has a geography, and the body has a geography.

As I listened to a 2005 song by the Seattle band Death Cab for Cutie a few days later, I considered how Ben Gibbard’s lyrics convey the powerful and then poisonous geography of romantic love. In the first half of “Marching Bands of Manhattan,” Gibbard proclaims the magnitude of his feeling. He imagines his arms spanning Manhattan and bringing the borough to his beloved. His mouth opens to introduce a marching band, which makes the streets and buildings resonate with the sound of his lover’s name. Omniscient, his open eyes see the beautiful views in every direction. Gibbard’s love grows his body to the scale of the city, and with love radiating forth, he becomes capable of altering New York’s waterways, filling its thoroughfares with sound, and visually absorbing the breadth of this changed landscape in a single, all-seeing view.

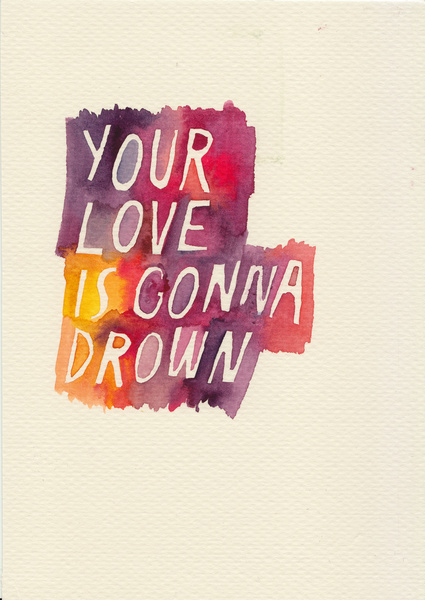

But in the second half of the song, love decays slowly, almost imperceptively, from within. The grand and public scale of Gibbard’s feeling and body is diminished to the intimate and interior spaces of bathroom plumbing and the anatomy of his lover’s heart. Pieced by a pinhole, this heart slowly drowns in sorrow. Gibbard says there is comfort in this dripping sound of sorrow entering the heart, and he seems himself to find solace in the sounds, repeating them several times so that the words accumulate, just like the growing pool of water/sorrow. While Gibbard actively reimagines the city, the lover is passive and confined inside, receiving sorrow instead of projecting love forth. She quibbles over nomenclature, and he envisions a city made new by his love. Despite the grand scale of the geography of his feeling, he ultimately can’t repair that tiniest of wounds. The scales and orientations of their love don’t match up.

I love how Gibbard’s songwriting helps us imagine the landscape of love, its features large and minute built up and brought down by feeling. I love how in this world, sentiment structures space.