The eye and lashes of a stuffed albino boar at Le Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris. Image by the author.

Paris, in April, was teeming with people: spring break tourists queuing up to see the famous sights and the politically passionate, or perhaps just paid, papering its telephone poles with images of and messages from politicians who would meet their fates in the elections just after we left. The elegant Museé de la Chasse et de la Nature, in Paris’s third arrondissement, felt far away from the busyness of the city’s congested streets and celebrated monuments. I have never seen such an exquisite marriage of objects, exhibition space, and graphics. But the presentation was anything but staid.

In the early part of the twentieth century, the French librarian and intellectual Georges Bataille lamented the loss of slaughterhouses in the city and the corresponding proliferation of museums. As we quarantined the violence and abjection of the abattoirs, museums took their place. We visited them ostensibly to see the cultural riches of the world, but we were really enacting purified, self-congratulatory performances of ourselves there, he wrote. Museums, in this way, reflected us and our relationship to culture and each other in a most ideal way. It seemed a flattering picture, but it was untrue, like Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray, who remains ever youthful while his portrait becomes increasingly disfigured as a result of his transgressions. Horror and obscenity and violence continue to persist below the placid surface, away from immediate view, Bataille argued.

Part of what I liked so much about the Museé de la Chasse et de la Nature was that some of the violence lingered, and the portrait was not always flattering. Instead of walking the hallowed halls of a neoclassical museum temple, I felt as though I were visiting the refurbished medieval hôtel of some eccentric and extraordinarily wealthy society figure, a man who might appear at any moment and invite me to select one of the many intricately carved guns on display and join him at the hunt or become his most dangerous game. René Descartes, that father of Enlightenment reason (he thought, therefore he was!) had espoused, the wall text informed us, a view of animals we now find untenable, even barbarous. Though animals were capable of physical sensation, they lacked the human ability to reason and were thereby, in his view, not conscious or aware. Glass eyes in taxidermy heads and sometimes bodies preserved after the animals’ deaths met us in each new room we came upon.

Instead of arranging objects chronologically, so as to narrate a story of artistic progression, the museum groups the collection by different animal species. In this way, historical objects mix with contemporary pieces to recount changing relationships between humans and other animals. In the unicorn room, visitors are introduced to a piece of writing by the fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Renaissance man par excellence, Leonardo da Vinci, whom we continue to revere for his astute scientific observation and engineering prowess. It may surprise you, as it did me, then, to learn that Leonardo believed in unicorns, and advised positioning a young, solitary maiden outdoors as the surest way to call them forth. Moving onto the dog room, we encountered both a painting of hounds on the trail of a fox as well as Jeff Koon’s porcelain Puppy, a kitschy trophy, if ever there was one, to man’s diminutive best friend. The puppy sits forward as if about to blow the horn that would summon his historical compatriots.

Instead of putting our own image on a pedestal, the Museé de la Chasse et de la Nature made me aware, at every turn, of its construction, painting a portrait of Western man through the lens of French aristocracy and its relationship to animals both exotic and domestic. I did not emerge feeling purified and light of heart, as Bataille described the crowds exiting the Louvre on Sunday afternoon, but both unsettled and enlivened by the strangeness of the place and its tales.

Later, as we continued to explore the city and in reading more when we returned, I learned of other stories about animals in Paris. The rhinoceros is an excellent case study of French fascination with exotic creatures. In September of 1770, an Indian rhinoceros, purchased by the governor of the small colony of Chandernagor, in West Bengal, India, arrived at Louis XV’s Royal Menagerie at Versailles, which had been operating since 1665. There it lived, with the rest of the king’s collection of exotic animals, until September of 1793, when a revolutionary, no doubt viewing it as an example of aristocratic excess, killed it with a sabre. Its remains were brought into the city, where, dissected and stuffed, it became part of the new natural history museum. It is still there today.

Louis XV’s taxidermic rhinoceros, now in the collection of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris. Image courtesy of Chateau Versailles.

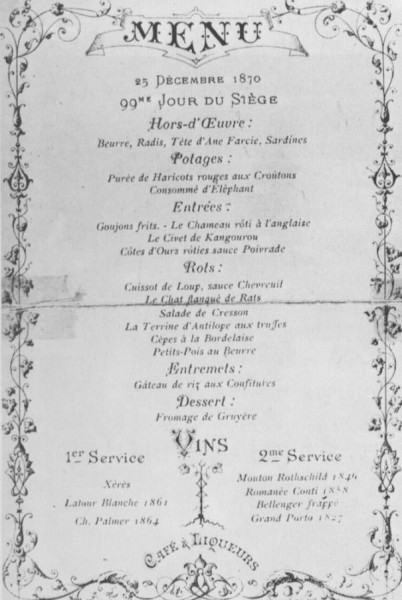

Other animals were rescued from the king’s menagerie and formed the basis of live collections at the Jardin d’Acclimation in the northern part of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris’s sixteenth arrondissement and at the Jardin des Plantes, just around the corner from the apartment where we were staying on the left bank. During the 1870-1871 Prussian siege of Paris, as the less fortunate resorted to eating cats, dogs, and rats, the famed chef Alexandre Étienne Choron cooked and served animals from these zoos in one of Paris’s finest restaurants, Voisin, on the rue Saint Honoré. His Christmas menu of 1870 included no rhinoceros, but donkey, elephant, camel, kangaroo, bear, wolf, and antelope were sent to the slaughterhouse and then prepared in high style. Nearly ninety years later, when Eugène Ionesco penned his 1959 existentialist drama, Rhinocéros, the French playwright reintroduced the rhinoceros yet again. In Ionesco’s play, those most seemingly sophisticated and successful are the first to transform into destructive rhinos, demonstrating the absurdity of modern life and the emergence of the bestial we suppress below the surface.

Christmas menu, 1870, at Chef Alexandre Étienne Choron’s Paris restaurant Voisin. Image courtesy of The Francofiles.

Perhaps no contemporary artist has probed the history of animal display more affectingly than photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto. Like the Museé de la Chasse et de la Nature, Sugimoto offers no facile historical narrative of progress and evolution. For his natural history diorama series, begun in 1976, he fashions photographs that appear to capture prehistory, before people started to write down what had happened. But of course photography is also a kind of writing, using light and chemical fixers to record. Far from an ancient technology, the medium was not invented until the middle of the nineteenth century. Sugimoto’s series are thus a double re-presentation, with photography capturing the exhibition techniques of natural history museums and those natural history museums re-creating, to the extent their scientific knowledge will allow, how we can best imagine rhinoceroses in their habitat millions of years ago. The photographer captures a history that never was, a place outside of time.

The artist has written in the catalog Hiroshi Sugimoto: History of History, a publication that accompanied his 2004 exhibition at the Smithsonian Art Museum’s Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur Sackler Gallery, “Ideas of deistic cosmogenesis beliefs that the cosmos was created by a god predominated throughout the world until only a few centuries ago. Even today, some people oppose the view that humans evolved from lesser animals. Hence, the scientific explanations offered here in this catalogue may be regarded as just another myth.”

The way we have related to animals — coveting the exotic, or coddling the domestic, for instance — has much to say about who we are, and how we think about ourselves and our place in the world. Both le Museé de la Chasse et de la Nature and Sugimoto compellingly mine the riches of that history and give us the tools to examine our historical and contemporary selves with open eyes.