Today, February 10th, is National Umbrella Day. I mark the occasion and celebrate the accessory, as my blog title is its namesake.

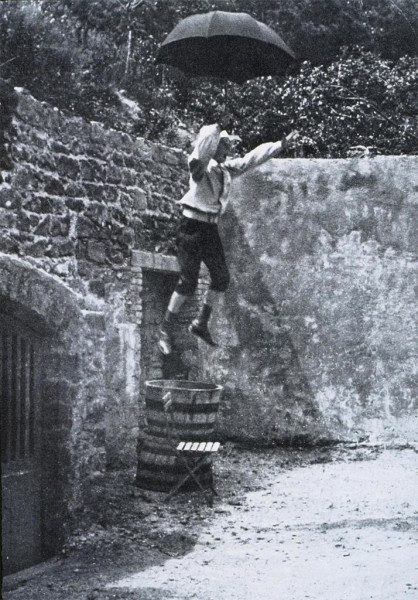

Zissou Jumping from a Wall with an Umbrella, early 1900s, by Jacques Henri Lartigue. Image courtesy of Artstor.

As I began to map out my art and architecture adventures and essays in August, I hunted about for a moniker. My partner suggested Yellow Umbrella, and I appreciatively snatched the name up. I like how it both conjures up my rainy Northwest location and invokes my actual cadmium yellow umbrella, a gift from a kind friend. It also brings to mind one of my favorite photographs, a picture by the Parisian boy Jacques Henri Lartigue. In the image, Lartigue’s brother, Zissou, is suspended, mid-air, between the top of a rough stone wall and the ground below. Zissou jumps to the earth, but with his knees slightly bent, his arms raised, and an open umbrella in hand, he looks like he could just as easily be ascending. Lartigue’s boyhood photographs capture voguish ladies, the heady velocities of automobile racing, and, above all, the exuberance of movement, adventure, and youth. They are at once universally representative of the enthusiastic spirit of children and unmistakably French cosmopolitan. The Lartigue brothers are younger versions of director Wes Anderson’s cinematic characters, affluent and intrepid before awkward teenage years have rendered them uneasy, if charming, eccentrics. With my umbrella in tow, I feel a bit like both Zissou, buoyed by my exploits, and Jacques Henri, hoping to capture them well.

The English word “umbrella” dates back to the early seventeenth century and has Italian and, before it, Latin origins that refer to shade or shadows. Indeed, the canopy of an umbrella can offer protection from both sun and rain. I think of my Yellow Umbrella as a mediator between myself and the world. It is both the object that shields me from environmental threats and the article that allows me to venture out in them. In its shelter, I observe and partake in my surroundings and, at the same time, provide myself with a small space of retreat, an island of private reflection.

Sam Spenser’s installation Bloom for the Wapping Project, 2007. Image courtesy of the London Evening Standard.

Beyond acting as an essential tool for my own rambles and impressions, the umbrella has also proven a ripe material for environmental artists. In the 2007 installation pictured above, Goldsmiths, University of London art student Sam Spenser planted unfurled umbrellas in an oak tree outside London’s Wapping Project. Part of a larger exhibition and immersive marketing experience called Yellow 1877 in honor of the signature color of champagne company Veuve Clicquot, which collaborated to produce the show, Spenser’s piece is called Bloom. Perched on the outstretched arms of the tree, the work’s umbrellas both resemble blossoming flowers and mimic champagne’s effervescent bubbles making their way weightlessly upward. Make it rain!

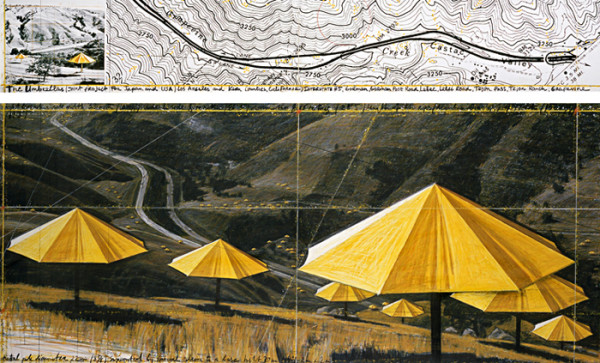

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas (Joint Project for Japan and USA), drawing from 1988 in two parts, pencil, pastel, charcoal, photograph by Wolfgang Volz, wax crayon, enamel paint, and topographic map. Image courtesy of the artists.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91. Image courtesy of the artists;

photograph by Wolfgang Volz.

Like Spenser, Bulgarian-born artist Christo has also referred to the umbrellas for his Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91 in floral terms. At the same time as the project’s blue umbrellas went up in Japan’s lush Ibaraki Prefecture, volunteers installed and then opened 1,760 golden umbrellas in southern California on “Blossoming Day” in October 1991. Sited along eighteen miles between Los Angeles and Bakersfield and harmonizing with the forms and colors of the area’s rugged desert hills, the large umbrellas were visible, like poppies in rolling fields, for eighteen days. Motorists observed them from highway I-5, a ribbon of road that snakes from the top of Washington state to the southernmost reach of California. Nineteen feet tall and twenty-eight feet in diameter, the umbrellas also provided shade for picnics. Ellen Walterscheild, a volunteer on the project, has recalled that one autumn morning during the run of the installation it rained, and visitors and project assistants alike gathered under Christo’s umbrellas to keep dry. Beneath one canopy, a wedding took place.

Collaborating over six years with project directors, a construction engineer, a project photographer, a project historian, and his now deceased French wife, Jeanne-Claude, who served, as always, as art dealer and business manager, Christo secured permission from numerous government agencies and private landowners to stage the project. With his team’s help, he designed the octagonal umbrellas, commissioned their production, and planned and executed their installation. As with all of his projects, Christo financed the twenty-six million dollar work privately through the sale of his preparatory drawings and prints. After the course of the installation, he recycled all materials. The makeshift communities forged by an army of kindred-spirited volunteers working to install and then monitor the large-scale work cordially disbanded once they had taken the umbrellas down.

Christo has characterized the Umbrellas as “the most profound expression of irrationality,” and the late British art critic Lawrence Alloway wrote that Christo’s installations “turn physical space into psychological response.”

So far, I have described and reflected on past projects, preserved by photography and, in Christo’s case, film. But now, I bring you a preview. Check your umbrella at the door of Seattle artist Susie J. Lee’s new exhibition Of Breath and Rain, which opens at the Frye Art Museum on February 18th. Stranger art critic Jen Graves has written frequently about Lee, a University of Washington MFA graduate. In an exhibition review from 2007, Graves asserts that Lee, “…already has articulated her major themes, and the rest is editing. Refrain is a maximal leap straight into love, loss, sex, death, cinema, spectacle, poetry, sound, and serious technology, but it feels like everything slipping through your fingers.” In its text about the upcoming show, the Frye Art Museum writes about Lee’s Rainshower, included in the show, “…Lee uses sound and light to immerse viewers in a virtual storm. Both the aural and visual patterns in the darkened gallery provide an ideal environment in which to reflect on time, love, loss, and memory.” I am prepared to be drenched in thought and feeling. Join me. Curated by Robin Held, Of Breath and Rain runs through April 15th.

In the meantime, enjoy the weather.