Films from 2011 were honored last week at the Hollywood Foreign Press Association’s Golden Globes ceremony. This morning, the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences announced its nominations for the 84th annual Academy Awards. In a nod to this season of cinema celebration, I consider, here, a gem of a film whose name you will not find on these aforementioned lists.

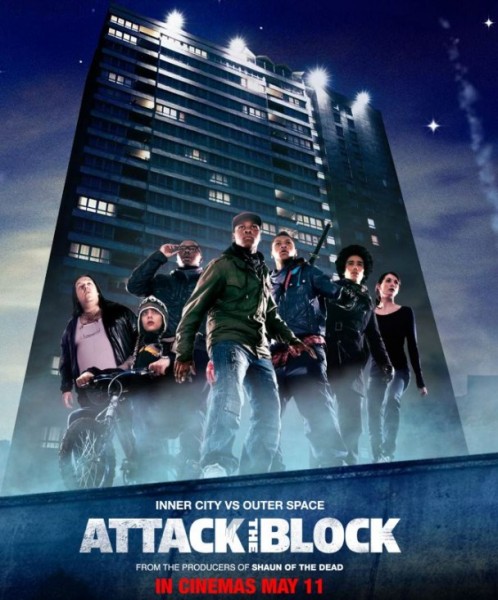

A group of teenage boys prepares to rob a woman in the film’s opening scene. Image courtesy of Attack the Block.

Attack the Block was released in the U.S. in late July. Written and directed by Joe Cornish, who grew up in south London’s Brixton neighborhood, the film opens by introducing us to a seemingly unsympathetic group of main characters: five teenage boys who mug a woman returning to her south London apartment and then proceed to pursue and kill an alien who has interrupted the robbery. They parade it proudly through the streets like the spoils of an urban war. When the young woman, Sam, shakily recounts the confrontation to a concerned neighbor, she cannot help but agree with the older woman’s characterization of her attackers as “fucking monsters.”

Are these adolescent aggressors the products of their environment, Wyndham Tower, a fourteen-story council house in Clayton Estate that characters in the film frequently call “the block,” or “the endz?” Resolutely so. The film plays like an extended turf war, with female characters allowing or denying access to individual apartments, while male characters often lay claim to the entire building. But as the movie unfolds, our image of the five young men and life in general in this residential tower block takes on subtler shades as well. A deep sense of solidarity has taken root and thrived here. Sam’s neighbor has never met her before, but welcomes Sam into her apartment. The five boys are sweetly affectionate, encouraging, and loyal mates. They verbally and physically defend each other, then Sam, and eventually their whole building from the menacing group of invading aliens — gorilla-wolf-monsters — who scale the imposing concrete fortress in pursuit of Moses, Pest, Dennis, Jerome, and Biggz.

The boys cleverly use their knowledge of Wyndham Tower to defend themselves and their neighbors. Biggz, for instance, jumps across elevated walkways to outwit a pursuing alien and hides in an impenetrable recycling dumpster, where he has taken shelter from a warring gang before. The film’s camera work uses quick shots that make these walkways look like mazes and potential traps. But though we do not know their ins and outs, the boys do. They use them as lookouts and skillfully navigate them on foot and bike to outpace the aliens. One of the film’s most unsettling scenes takes place during a rare moment of spacial uncertainty, when Jerome becomes disoriented in a smoky hallway. His momentary loss of bearings separates him from his friends and endangers him. Cornish uses hallway lights that flicker alive or die out to moody effect, but “the block” is also the site of personalized front doors and functioning families, which include Dennis’s father, who insists that his son take the dog out, and Jerome’s sister, predictably annoyed with her teenage brother as she studies for an upcoming exam.

Children playing cricket at Robin Hood Gardens, designed by architects Peter and Alison Smithson, in the 1970s. Image courtesy of Tree Hugger; photograph by Sandra Lousada.

The demolition of part of the Pruitt-Igoe complex, March 1972. Image courtesy of Designerly Thinking.

In April 1957, British architects Peter and Alison Smithson wrote in the magazine Architectural Design that their practice “tries to face up to a mass-production society and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.” New Brutalism, the label applied to the Smithsons’ work, involved an honest, rugged presentation of inexpensive materials to provide democratic, economical housing after widespread wartime destruction in London. The Smithsons designed and wrote frequently during their long careers, but built little. One of their surviving projects is Robin Hood Gardens, a housing complex in Poplar, London, designed between 1964 and 1970 and finished in 1972. It resembles Attack the Block‘s Wyndham Tower in style, building material, and scale. In 2009, British Minister of Culture Andy Burnham refused, in the face of a recommendation from the organization English Heritage, to grant Robin Hood Gardens a certificate of immunity that would spare it from demolition. Many see the project, like the Pruitt-Igoe complex in St. Louis, the subject of another recent film, as yet one more example of failed Modernist housing for working-class people. Plans are now in the works to raze Robin Hood Gardens and replace it with new residential highrises.

The social ills that have plagued places like the fictionalized Wyndham Tower, Robin Hood Gardens, and Pruitt-Igoe are real. The August eruption of violence and riots first in London and then across Britain testifies to an underlying social malaise that concentrates in areas where highrises dominate the urban landscape. But there are other narratives as well, stories that speak to subtler behaviors, practices, and adaptations happening in high-density housing.

A Detroit woman photographed in her home, among her things, for Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies. Image courtesy of Placement.

Recently, a new organization called Placement began its first project in Lafayette Park, Detroit. Their focus is the people who live and work in Lafayette Park, site of a 1940s urban renewal project that resulted in the largest concentration of Mies van der Rohe buildings in the world. Placement has published their findings in a book called Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies. They write, “Lafayette Park today is one of the most racially integrated neighborhoods in Detroit, a city with the distinction of being the most segregated in the country for African-Americans. The neighborhood remains economically stable despite the fact that Detroit has suffered enormous population loss and bears innumerable signs of strained city services.”

Architectural design alone cannot solve social problems like high unemployment, destructive drug use, and lack of parental involvement. Flush with the right resources, however, it can provide setting for healthy communities. These might not always arise in ways we can easily predict. As New York Times architectural critic Nicolai Ouroussoff wrote in 2009 in favor of an architectural overhaul of the Smithsons’ Brutalist Robin Hood Gardens, “Condemning an entire historical movement can be a symptom of intellectual laziness. It can also be a way to avoid difficult truths. Architecture attains much of its power from the emotional exchanges among an architect, a client, a site and the object itself. A spirited renovation of Robin Hood Gardens would be a chance to extend that discourse across generations.”

In an election year like this one, political rhetoric can become inflated, as when we speak of “illegal aliens” or “class warfare.” Attack the Block reminds us that the monsters are not the people among us and that even those who flirt with criminality can change their lives if only given the opportunity. The film includes street slang, exaggerated gore, and casual drug use. It also showcases clever editing, great humor, a thoughtful consideration of the exchange between large-scale mid-century architecture and its residents, and characters for whom you will ultimately want to cheer.

Believe.