Leaves crunch underfoot. (I seek them out and jump with delight upon them.) The cherry tomatoes are so sweet, and dahlias finally begin to bloom, but the warm sun belies autumn’s coming.

This week, I went to see the Seattle Art Museum’s shows Beauty and Bounty: American Art in an Age of Exploration and Reclaimed: Nature and Place Through Contemporary Eyes. As has so often been the case with SAM’s strategy to present related shows in tandem, the two exhibitions amplify and enliven one another. The brash melodies of eyewitness participation and artistic dramatization in Beauty and Bounty become echoes and counterpoints for contemporary artists considering their own relationships with the Western landscape in Reclaimed.

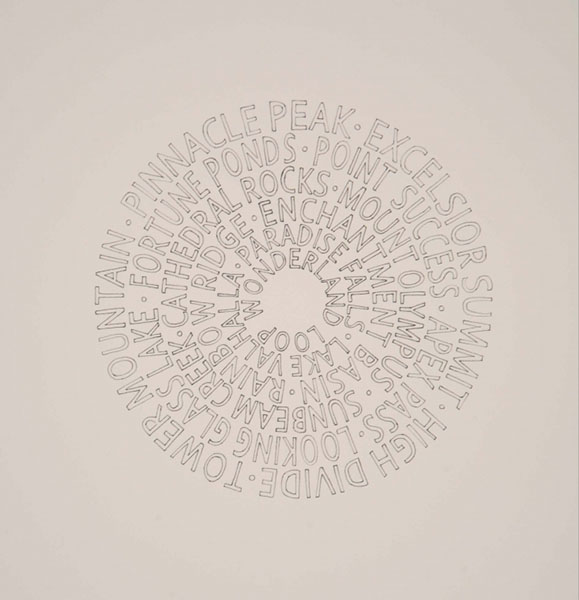

Victoria Haven’s drawing Northwest Field Recording – Washington 7 inch A side. Image courtesy of the artist.

Past the mighty Bierstadt paintings and toward the back of Beauty and Bounty, exhibition-goers donned lenses to view stereoscopes of the Western landscape made in the late nineteenth century. Popular with so-called “armchair travelers,” those who could journey only vicariously, the pairs of photographs, each taken from a slightly different angle, give viewers impressions of spatial depth when seen together. A few galleries later, in Reclaimed, Victoria Haven’s side-by-side drawings Northwest Field Recording, A Side and B Side employ Washington place names to show how we have used language to assign meaning to our perceptions and experiences of the natural world. In the A Side drawing on the left, the names, which include “Enchantment Basin,” “Paradise Falls,” and, at the center ring of her circular drawing, “Wonderland Loop,” are positive in association. The names she has drawn for the B-side composition on the right are, on the other hand, negative, evoking fear over wonder. While the stereoscope pairs in Beauty and Bounty transform a two-dimensional visual encounter into a three-dimensional experience, Haven’s paired drawings of words in Reclaimed throw into relief the dualities of our complex relationships with a single region.

There are resonances like this throughout the two shows. Another prime example is the way photographer Glenn Rudolph seems to respond to the legacy of nineteenth-century photography. Rudolph’s evocatively beautiful black-and-white prints capture the ruins of railroad lines snaking through the Northwest landscape, where pioneering photographers like William Henry Jackson had once championed their coming.

The exhibitions feature the visual, but with all this call and response, I heard music.

Beauty and Bounty and Reclaimed are up at the Seattle Art Museum through September 11th.